- Startpagina tijdschrift

- Volume 95 - Année 2026

- No 1

- Advanced Electrochromic Materials: a (Smart) Window on the World of Tomorrow

Weergave(s): 11 (4 ULiège)

Download(s): 0 (0 ULiège)

Advanced Electrochromic Materials: a (Smart) Window on the World of Tomorrow

Documenten bij dit artikel

Version PDF originaleAbstract

The energy demand of buildings can be significantly reduced by integrating energy-efficient technologies that limit overall energy consumption. Smart windows are devices capable of dynamically controlling indoor luminosity and temperature in response to external factors such as weather conditions, seasonal variations, or user preferences. Among the various materials and formulations investigated, electrochromic materials—characterized by their ability to reversibly switch between optical states upon the application of an electric potential—have been extensively studied for smart-window applications. In this work, the mechanisms governing the optical activity of such materials are discussed, with particular emphasis on dual-band formulations, which enable the dynamic and independent control of light and heat supplied to buildings, respectively related to transmitted visible (VIS) and near-infrared (NIR) solar radiation. Finally, the main results of the author’s thesis are presented, highlighting the dual-band electrochromic behavior of a distinctive molybdenum–tungsten mixed oxide formulation, whose potential for this application had never been investigated before, to the best of our knowledge.

Inhoudstafel

Received: 19 April 2025 – Accepted 5 November 2025

This work is distributed under the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 Licence.

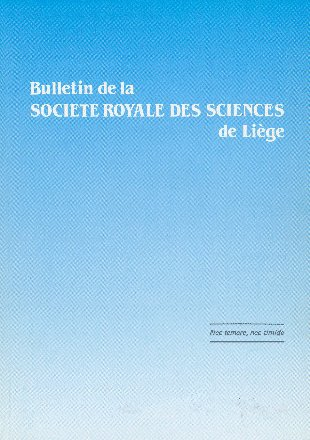

1. General Context and Environmental Insights

1In the current context of ecological and economical concerns, our societies are facing, managing our energy expenditure is of the utmost importance, both in terms of how much is used and what it is used for. While the transportation and industry sectors are responsible for a significant proportion of the global energy demand, it is the residential and commercial building sectors that are the most energy-consuming ones, with 40 % of the global demand (Fig. 1) [1, 2]. Moreover, the majority of their energy expenditure is directed towards the control of indoor temperature and luminosity through heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) and lighting appliances.

Figure 1: Pie charts breaking down the energy demand by sectors (a) in Europe in 2022 [1] and (b) in the United States in 2023 [2].

2Given this context, energy efficient technologies have been developed in the last decades to improve the energy demand of buildings and move towards net zero energy housing and commercial structures. Among those, some of the most widespread are LED bulbs [3], solar panels [4, 5], advanced thermal insulation [4], geothermal heat pumps [4, 5], and green roofs [4, 6] to name but a few. However, with modern architecture favoring large windows [7, 8], sometimes even covering the whole facade of buildings, efficient fenestration technologies are sought after in order to avoid large energy loss.

3To address these challenges, various solutions have been developed over the years. Some of them are already widely implemented, such as double- and triple-pane windows [9], and low-emissivity coatings [9–11]. These technologies allow a better control over the heat transmitted into the building by filtering out the near-infrared (NIR) solar radiation while allowing visible (VIS) light to pass through [4, 10]. However, they are constrained by their passivity, lacking the ability to change their optical properties in response to external factors influencing the heat and luminosity needs, such as weather conditions, seasons, or the preference of the user, ultimately limiting their energy efficiency [9]. Active materials, switching between optical states when exposed to a given stimulus, could therefore greatly enhance the energy saving properties of such windows.

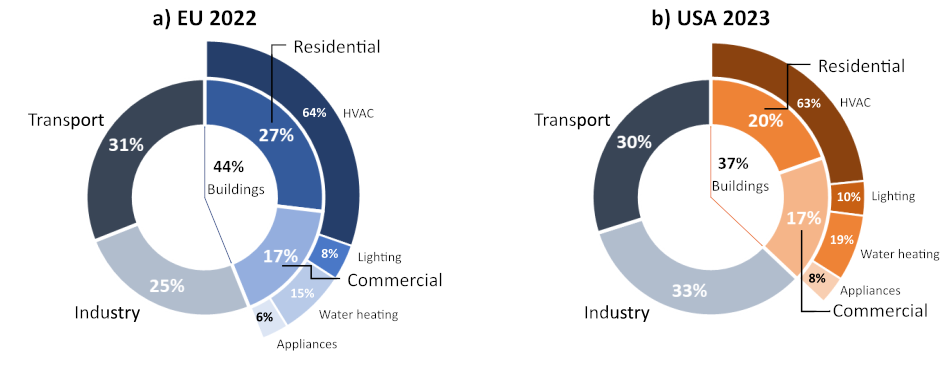

4To do so, chromogenic materials can be implemented, notably photo-, thermo- and electrochromic materials, in which a switch in the optical properties is respectively activated by a change in light, temperature and electrochemical potential [9], as illustrated in Fig. 2. However, photo- and thermochromic materials react to natural stimuli, which are not controllable by the user to tune the properties of the glazing. On the other hand, electrochromic materials require an external source of energy to be activated, but allow a fine control of the optical characteristics of the window, in a controllable and “on-demand” way.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the working principle of chromogenic smart windows.

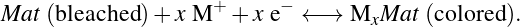

5The bias required to activate the electrochromic effect is nevertheless usually very low, typically in the range of a few volts; therefore, the small loss in energy necessary for the operation of the window can be largely compensated by the potential energy savings arising from its enhanced adaptability towards external conditions [12]. Previous reports confirmed this through simulations, showing a superior energy efficiency in electrochromic materials in comparison to photo- and thermochromic ones, in both terms of lighting and temperature control [12]. Given their greater degree of control and energy-saving potential, electrochromic materials have been applied in commercially available “smart windows”, such as those produced by Saint-Gobain (SageGlass [13]) and AGC Glass (HalioTM [14]), switching between a transparent state and a dark blue colored state (as illustrated in Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Effect of an electrochromic window, as imagined in the premises of GREEnMat-ULiège.

2. Electrochromic Materials for Smart Window Applications

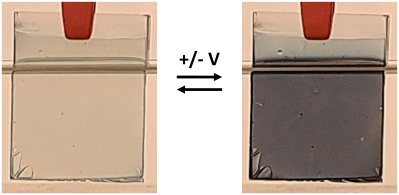

6The optical response observed in the two examples discussed above arises from the electrochromic properties of the active material implemented in the glazing. Electrochromism is defined as the ability of a material to reversibly switch between optical states upon application of an electrochemical stimulus [9, 15]. In the case of conventional materials, such as those applied in commercially available glass, the active compound usually switches between a high-transmittance (“bleached”) and a low-transmittance (“colored”) state (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Pictures of an electrochromic film switching between its bleached (left), and colored states (right).

7Electrochromic properties have been reported for a number of materials, which can be classified in four main categories [9, 16–21]:

-

organic molecules, such as viologens;

-

conjugated conductive polymers, such as polypyrroles and polythiophenes;

-

metallic complexes, such as Prussian blue;

-

inorganic metal oxides, such as WO3, NiO, V2O5.

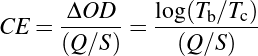

8In the context of smart windows, inorganic metal oxides are predominantly used due to their superior durability under UV radiation and their high stability against heat and electrochemical cycling (windows can reach temperatures of up to 50 °C during summer) [9, 22–24]. Among metal oxides, the transition metal oxides of W, Mo, V, Ir and Ni show excellent electrochromic properties, with WO3 being the most extensively studied material in the field [16]. This material reportedly exhibits excellent performance, with an optical transmittance contrast of up to 98 % in the visible range between its transparent and dark blue state [22], stability over 100,000 coloration/bleaching cycles [22] and a high coloration efficiency of 150 cm2/C [25]. The coloration efficiency (CE) is a figure of merit used to quantify and compare the efficiency of electrochromic materials, and is defined as the intensity of the optical transmittance modulation between the bleached and colored states per unit of charge,

9where ΔOD is the change in optical density, defined as the logarithm of the ratio between Tb and Tc, the transmittance in the bleached and colored states, resp., and Q is the charge density, normalized by the area S of the investigated film.

10In conventional materials, such as WO3, the electrochromic coloration/bleaching arises from the insertion and extraction of cations M+ (e.g., H+, Li+, K+, Na+, etc.) into and from the crystal lattice upon the application of an electrochemical bias [9]. The concomitant insertion of a cation and an electron—to retain the electroneutrality of the material—results in the reduction of W from its 6+ transparent state to its 5+ colored state [9] according to the reaction

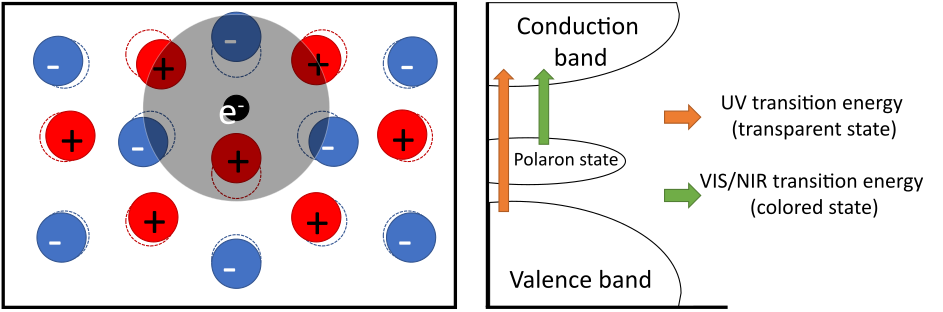

11Several mechanisms have been proposed as early as in the late 1950s to explain the absorption responsible for the coloration of WO3; however, the most widely accepted is the polaron model [26–28]. This model describes the interaction between an electron and a phonon—a local deformation in the crystal lattice—resulting in the formation of a potential well that localizes an electron via phonon–electron coupling, creating a quasiparticle called a polaron [29]. The coupling between the electron and the surrounding phonon leads to the creation of a new populated electronic (polaronic) state within the band gap of the material (Fig. 5). The electronic transition between the polaronic state and the conduction band gives rise to absorption at lower energy, corresponding to longer wavelengths, i.e., shifting from the UV (transparent state) to the VIS/NIR (colored state) range [30].

Figure 5: Schematic representation of the lattice deformation induced by the insertion of an electron, and the resulting electronic band appearing in the band gap.

12The polaronic state in WO3 typically lies in a region covering both the VIS and NIR ranges of the solar spectrum, leading to the simultaneous modulation of both luminosity and heat [9]. In order to improve the functionality of electrochromic materials and the energy efficiency of smart windows, it would be interesting to find a way to modulate VIS and NIR radiations selectively and independently. Indeed, simulations show that conventional smart windows implementing materials such as WO3 can result in savings of 40–170 kWh/m2 per year [31]. Meanwhile, a similar device with the ability to selectively control the transmittance of both VIS and NIR solar flux should lead to savings in the range of 60–300 kWh/m2 per year [32], nearly doubling the efficiency of the window. This is mostly due to the improved management of energy expenditures in buildings: with conventional materials, when the device is turned on, both VIS and NIR radiations are filtered out, which means that if the window is used in summer to block the heat from entering, lighting appliances have to be turned on to compensate for the luminosity loss [9]. On the other hand, if the device is used for privacy reasons (by making it colored and more opaque) or to avoid glares in winter, the small portion of solar heat (NIR) reaching the building is filtered out and indoor heating is required to maintain a similar temperature level in the room.

3. Towards Greater Energy Savings: Enhancing Functionality with Plasmonic Materials

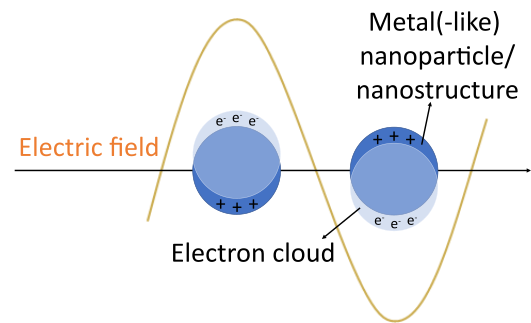

13To achieve the sought selective modulation, new materials and formulations were investigated and developed; in particular, plasmonic materials have attracted the attention of the scientific community. The plasmon is the quasiparticle associated with the collective oscillation of free charge carriers (electrons or holes) in metals and doped semiconductors, upon interaction with an electromagnetic wave. If the frequency of the incident light meets the resonance conditions of the material, the electric field is locally enhanced and a strong optical absorption ensues [9, 30, 33–35]. The oscillation is mostly expressed at the surface of the particles and thus is referred to as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [34]. If this SPR phenomenon is spatially confined in a nanoparticle or a nanostructure, the plasmon becomes a non-propagating standing wave, also known as localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR—see Fig. 6) [34].

Figure 6: Schematic representation of the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) in (metal) nanoparticles in the presence of an electric field.

14The frequency of the oscillation depends on numerous properties of the material, such as the size and morphology of the particles, their composition, the presence of doping agents—in particular their concentration and distribution (homogeneous or segregated, as in core-shell systems for example)—the dielectric constant of the surrounding environment, and the concentration in free charge carriers [30, 33, 34]:

15where ωp is the plasma frequency, n is the concentration of free charge carriers, e is the charge of an electron, 𝜀ε0 is the permittivity of free space and me∗ is the effective mass of an electron.

16In noble metals, the concentration of free electrons typically lies in the range of 1022 to 1023 cm−3, resulting in plasmonic absorption taking place in the visible range [34]. By contrast, doped semiconductors exhibit lower free carrier concentrations, ranging from 1018 to 1021 cm−3, effectively reducing their plasma frequency and shifting their optical signature into the NIR region [34, 35]. In addition, the lower carrier concentration in these materials can be tuned, whether it is in situ through chemical doping during synthesis, or ex situ via post-synthetic application of an electrochemical bias [34]. Therefore, the possibility to modify the optical properties of the material upon the application of an electrochemical bias makes such doped semiconductors promising candidates for electrochromic applications. In particular, such doped metal oxide compounds could be implemented for NIR-selective applications.

17The first semiconductor formulations investigated for their NIR-selective plasmonic properties were the transparent conductive oxides (TCO) [36, 37]. Materials in this group, such as aluminum-doped zinc oxide (AZO) [9, 33, 35], indium-doped cadmium oxide (ICO) [38] and tin-doped indium oxide (ITO) [9, 33, 39], exhibit LSPR responses in the infrared region, from 1600 nm to 5000 nm [38]. These properties enable independent filtering of NIR light, as demonstrated in the work of Delia Milliron and her team. Their research initially focused on the NIR-selective plasmonic electrochromism of ITO [39, 40], showing remarkable performance of this material, with a large optical contrast in the NIR region (greater than 40 %) while VIS light remained unaffected.

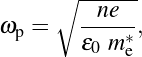

18Building on this first proof-of-concept, further work by her team proposed the formulation of a composite material allowing for the selective and independent modulation of VIS and NIR radiation, a functionality also referred to as a “dual-band” activity. By combining plasmonic ITO with NbOx, a conventional electrochromic material behaving similarly to WO3, they demonstrated the ability to selectively and independently control the transmittance of the film for both VIS and NIR wavelengths [41]. In their system, ITO nanoparticles are dispersed within a glass matrix of NbOx, effectively embedding the nanocrystals in the structure. When an oxidizing potential is applied, all materials are in their transparent, bright state. Applying a slightly reducing potential preferentially activates the optical activity of the ITO nanocrystals and only the NIR is filtered out, corresponding to the so-called cool state [41]. Further decreasing the bias to more reducing potentials leads to the reduction of NbOx into its colored, dark state, simultaneously modulating both VIS and NIR regions of the spectrum [41]. This two-regime dual-band activity arises from the different absorption mechanisms at play in the two materials—polaronic in NbOx and plasmonic in ITO—which are activated at different potentials, with the NIR-selective plasmonic activity occurring first, followed by the VIS/NIR polaronic modulation at greater biases.

4. Optimizing the Optical Properties of Plasmonic Formulations

19Although these breakthroughs demonstrated the feasibility of dual-band electrochromic modulation, the plasmonic resonance of ITO and other TCOs limited the efficiency of these systems. Indeed, more than half of the NIR solar intensity lies in the 750–1250 nm range [33, 35, 36], with the plasma frequency of TCOs appearing too far into the NIR to provide an efficient modulation of NIR wavelengths. In response, new formulations were developed and investigated, looking for materials displaying LSPR frequency in the 750–1250 nm interval of interest. In particular, materials derived from WO3 sparked the interest of the scientific community, with WO3−δ and CsxWO3 being the two most promising candidates, as they offer plasmonic absorptions starting at 900 nm and 1050 nm, respectively [38].

20With plasmonic properties in the 750–1250 nm range, WO3−δ was successfully applied as a NIR-selective material in a nanocrystal-in-glass configuration by Milliron and co-workers, in combination with conventional NbOx [42]. This composite formulation showed enhanced electrochromic performances in comparison to ITO/NbOx, improving the modulation in both the VIS and the NIR ranges as a function of the applied potential, reaching 70 % at 2000 nm and 85 % at 1250 nm in the cool state, and 70 % at 550 nm in the dark state [42].

21Additionally, WO3−δ and CsxWO3 offer another significant advantage in over TCOs: being derived from WO3, known for its conventional electrochromic properties, these plasmonic derivatives are capable of dual-band electrochromism within a single material formulation. This was experimentally verified, notably by Lee and co-workers [43–45], who observed the two-regime behavior in WO3−δ, with switching from the bleached state to the cool state and then to the dark state, thereby combining the optical activity of conventional and plasmonic materials in a single formulation (Fig. 7). Besides WO3−δ, other formulations have been shown to exhibit dual-band electrochromism, notably Nb12O29 [46] and Nb-doped TiO2 [47, 48].

Figure 7: Illustration of the different optical states met in conventional and plasmonic electrochromic materials as a function of the applied potential, and responsible for the consecutive modulation of the NIR and VIS regions.

5. Mixed Molybdenum–Tungsten Oxide, a Promising Photocatalyst

22Besides CsxWO3 and WO3−δ, oxygen-deficient mixed molybdenum–tungsten oxide (Mo1−yWyO3−δ, hereafter referred to as “MoWOx”) has attracted attention due to its reported plasmonic properties [49–58]. Indeed, previous work by Yamashita and co-workers reported a large increase in the optical response of this mixed formulation compared to the parent oxides (WO3−δ and MoO3−δ), with 20- and 16-fold increases, respectively, in the 750–1250 nm spectral range of interest [49]. According to the authors, this large increase in absorption arises from the creation of oxygen vacancies, boosting the plasmonic response of the material, as well as the formation of reduced species (X6+ → X5+, with X standing for W or Mo), responsible for the polaronic states discussed previously [49]. However, before our recently published research works [59–61], MoWOx had been thoroughly investigated as a (photo)catalytic material [49–52, 54–56], for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) [57] and NIR-shielding [53], but had never been applied as a dual-band electrochromic material.

23In the framework of dual-band electrochromism, MoWOx is identified as a promising candidate, combining oxygen vacancy doping and molybdenum substitution, both identified as pathways towards improved functionality in WO3-based formulations. On one hand, the common strategy employed to induce plasmonic properties in MoWOx formulations relies on the formation of oxygen vacancies [35, 62, 63], in particular for (photo)catalytic applications. On the other hand, Mo doping or substitution has been reported to improve the optoelectronic properties of stoichiometric (non-plasmonic) WO3, specifically in the scope of conventional electrochromic applications (with reportedly improved contrast, coloration efficiency, and durability to electrochemical cycling) [64–72]. Among the surveyed doping candidates reported in the literature (e.g., Ni, Mn, Ce, Se, Y, Pd, etc.) [56], Mo emerges as a promising species due to its physicochemical properties: like W, it belongs to group 6 (Mo and W have similar electronic band structures) and it has a comparable ionic radius (Mo = 7.3 Å, W = 7.4 Å), which facilitates its efficient substitution into the crystal lattice [51, 53, 55].

24In this context, the combination of those two approaches—oxygen vacancy doping and Mo substitution—should lead to improved optoelectronic properties, on which the electrochromic performances of the materials depend, and enhanced functionality through the support of the plasmonic features required for dual-band electrochromism.

6. Assessment of the Dual-Band Electrochromism in MoWOx

6.1. Characterization of powder samples

25The synthesis, deposition and characterization of MoWOx for its electrochromic performances have been investigated in several studies [59, 60] as well as in my PhD thesis [61]. These studies highlight the distinctive electrochromic properties of MoWOx, especially its ability to selectively modulate the VIS and NIR spectral ranges.

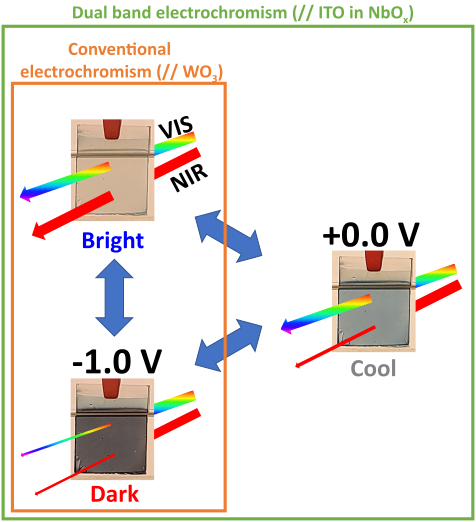

26Preliminary characterization indicated that the best MoWOx formulation has a Mo/W ratio of 2:1, and was synthesized via 1 hour of solvothermal treatment at 160 °C, adapted from the work of Yamashita et al. [49, 50]. The powder obtained from this reaction could be characterized by scanning and transmission electron microscopy (SEM and TEM), and exhibits an urchin-like morphology, with an average diameter measured at 1.5±0.5 µm (Fig. 8a), and nanostructures (nanorods at the surface) to support LSPR phenomena. In comparison, a reference WO3−δ formulation synthesized in the same conditions yields aggregated nanospherical particles (Fig. 8b).

Figure 8: TEM micrographs of particles of MoWOx 1h (a) and WO3−δ 1h (b). The inset in (b) shows an aggregate at greater magnification.

27Besides its interesting morphology, the recovered MoWOx powder exhibits a deep dark blue hue (Fig. 9), reported to appear in substoichiometric materials, while WO3−δ appears as a green powder (halfway between the typical yellow color of stoichiometric WO3 and the dark blue tint of substoichiometric oxides).

Figure 9: Pictures of the two as-synthesized powders: MoWOx 1h (left) and WO3−δ 1h (right).

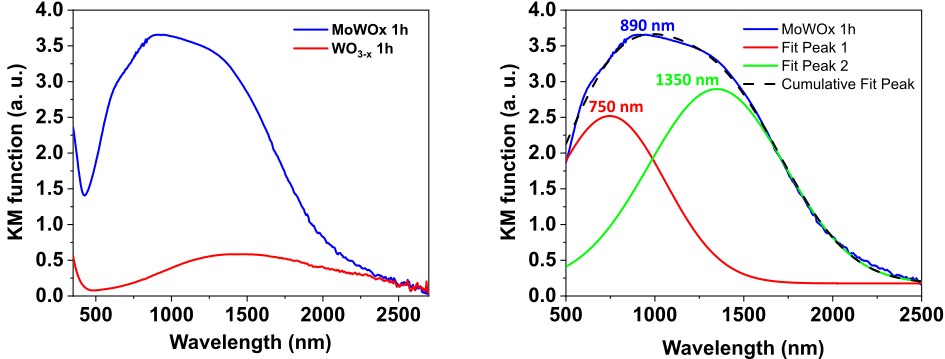

28The optical absorption spectrum of MoWOx exhibits a large absorption peak stretching over both VIS and NIR regions and centered around 890 nm [60, 61]. In comparison, the optical signature of WO3−δ appears to be much less intense (Fig. 10), as expected from Mo substitution in the previous results of Yamashita et al. [49, 50].

Figure 10: Absorption spectra of MoWOx 1h and WO3−δ 1h powders (a), and mathematical fitting of the optical signal of MoWOx 1h (b).

29Moreover, the MoWOx signal seems to be comprised of two superimposed contributions, as indicated by the shouldering on both sides of the apex. The mathematical deconvolution of the signal, presented in Fig. 10, highlights two peaks: a first one at 750 nm and a second one at 1350 nm. Since the plasma frequency of WO3-derived formulations is expected to lie in the NIR range, the rightmost contribution is presumably the plasmonic one, while the one at 750 nm corresponds to polaronic states arising from the formation of W5+ and Mo5+ reduced species during the synthesis process, as previously stated and reported by Yamashita and co-workers.

6.2. Electrochromic performances of films

30As MoWOx displays promising properties both in terms of morphology (presence of nanostructures at the surface of the urchins) and optoelectronic properties (high concentrations in unpaired electrons resulting in strong absorption), this material could be processed into thin films, using wet-coating methods such as spin coating, in order to characterize its electrochromic performances.

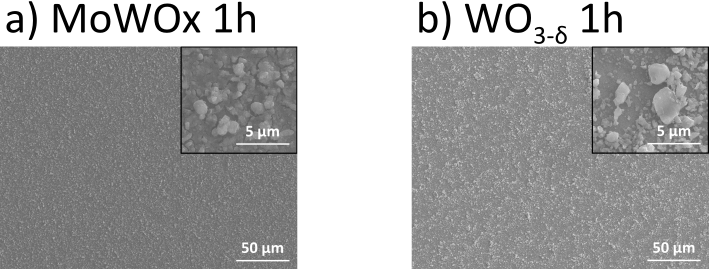

31Micrographs of the films in Fig. 11 show a similar morphology in both thin layers, with MoWOx particles and WO3−δ aggregates evenly distributed on the surface of the substrate, and resulting in comparable thicknesses of 0.84±0.03 µm for MoWOx and 0.87±0.03 µm for WO3−δ. These samples were then investigated for their electrochromic performances through in situ spectroelectrochemistry.

Figure 11: Top view SEM micrographs of films produced from MoWOx 1h (a) and WO3−δ 1h (b). The insets show details at a greater magnification.

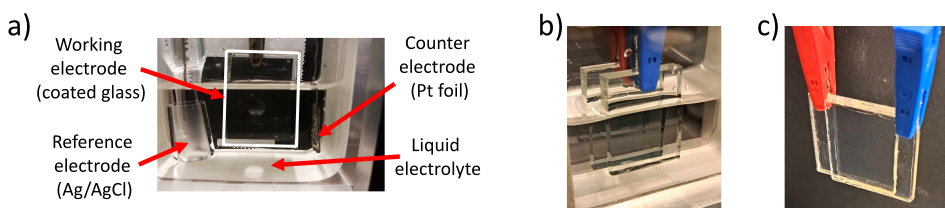

32For this purpose, the films were placed into a three-electrode cell configuration, comprising of (1) the working electrode (the sample), (2) a counter electrode (a piece of platinum foil), and (3) a reference electrode (Ag/AgCl). These three elements were immersed in an optical glass cell containing an electrolyte (0.5 M LiClO4 in propylene carbonate (PC) in the present case), and connected to a potentiostat/galvanostat. The cell was placed inside the analysis chamber of a spectrophotometer, allowing the simultaneous and coupled monitoring of electrochemical and optical properties.

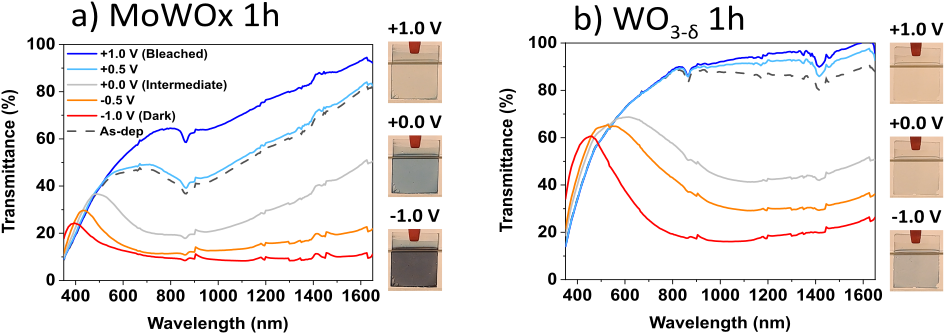

33The spectroelectrochemical spectra acquired for MoWOx and WO3−δ are presented in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: SEC transmittance spectra of MoWOx 1h (a) and WO3−δ 1h (b) films biased in LiClO4/PC, as a function of the applied potential. Pictures of the films in the bleached (+1 V), intermediate (0 V) and dark (−1 V) states are shown as insets next to the corresponding spectra.

34For each formulation, the optical transmittance is measured at three potentials: +1.0 V, 0.0 V and −1.0 V. As expected from the existing literature, WO3−δ exhibits dual-band electrochromism, with three distinct optical states: the most oxidized bright state at +1.0 V, transparent in both VIS and NIR regions, the cool intermediate state at 0.0 V, displaying the NIR-selective absorption linked to the activation of the plasmonic properties of the material, and finally, the dark state at −1.0 V, colored in both VIS and NIR ranges upon reduction of the tungsten by the inserted cation/electron pairs. In the case of the MoWOx formulation, three optical states are once again identified, with a NIR-preferential intermediate state at 0.0 V and a dark state at −1.0 V; however, the initial oxidized state (at +1.0 V) appears to differ from that of WO3−δ. Indeed, in the case of the mixed oxide, transmittance remains high in the NIR range, but partial absorption occurs in the VIS region, corresponding to a so-called warm state—a phenomenon that, to the best of our knowledge, has not previously been reported for W- and Mo-based electrochromic oxides. This novel functionality of MoWOx could enhance energy efficiency when applied in smart windows, by increasing the device’s adaptability to external conditions such as weather and seasonal variations. In particular, this warm initial state could prove useful in high-latitude regions and cold climates, as it maximizes heat transmission into the building while preventing blinding glares caused, for example, by a fresh layer of snow. It is hypothesized that the emergence of this unusual warm state arises from the large increase in absorption in MoWOx upon Mo–W mixing, which limits the maximal transmittance achievable close to its peak optical response (850–900 nm).

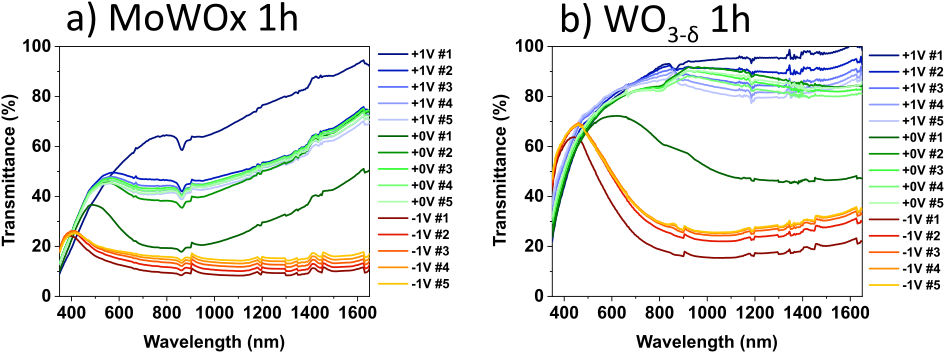

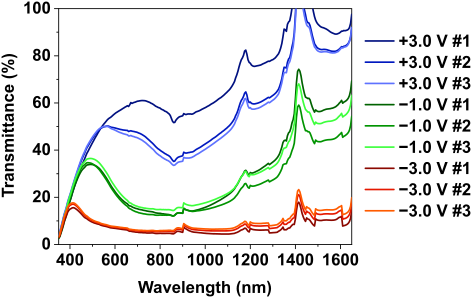

35With their dual-band activity successfully demonstrated, WO3−δ and MoWOx were further investigated for the reversibility of the observed optical phenomenon, as electrochromism corresponds, by definition, to the reversible change in a material’s optical properties upon application of an electrochemical bias. Films of both oxide formulations were cycled in LiClO4, and exhibited limited stability, transitioning from three optical states to only two from the second cycle already, as can be seen in Fig. 13.

Figure 13: SEC transmittance spectra of MoWOx 1h (a) and WO3−δ 1h (b) films biased in LiClO4/PC, as a function of the electrochemical cycling.

36Indeed, going from the dark state back to the bright state, reversibility is not retained and the bright and cool states appear to merge into a single one. In contrast, the dark state is stable over several cycles. The disappearance of the intermediate state (expected to arise from plasmonic phenomena) suggests a likely modification of the material’s surface properties that support the plasmonic features. This behavior could be due to a number of factors, such as dissolved species in the electrolyte (e.g., oxygen and water) which may react with the active layer and irreversibly modify its surface properties, thereby inhibiting plasmonic capabilities.

7. Design of Proof-of-Concept Devices

37Typically, an electrochromic device comprises five layers: an electrolyte, a working electrode, and a counter electrode, with both deposited onto conductive substrates. Having successfully demonstrated the peculiar electrochromic properties of MoWOx in a three-electrode setup, the design of a complete device involving this innovative material can be envisioned. For this purpose, highly efficient counter-electrode materials were developed at GREEnMat, based on CeO2, a well-known optically neutral counter-electrode material, especially in the electrochromic field. Briefly, molybdenum-doped CeO2 films were produced via ultrasonic spray pyrolysis, yielding highly homogeneous and transparent films with a high charge-storage capacity (cation storage in this case). The results of this particular work is discussed in a dedicated article [73] and highlighted an optimal Mo doping of 6 at.%, demonstrating excellent performances, such as a 93 % transmittance at 550 nm and a capacity of 28 mC/cm2—both surpassing previously reported values in the literature [73].

38With both working and counter electrodes available, devices can be assembled to investigate the behavior of these materials in “real-working” conditions. In a first step, liquid devices are devised, by immerging the two films (active and counter electrodes), facing each other, in the same LiClO4/PC electrolyte used for the previous characterizations of standalone films. This liquid setup exhibits almost identical properties to those of the active film alone, showing the three working states at similar transmittance levels, and highlighting the great performances of the CeO2-based counter electrode, not limiting the expression of the dual-band properties of MoWOx (Fig. 14).

Figure 14: Transmittance spectra of the MoWOx/CeMo6 liquid setup as a function of the applied potential, and repeated over three electrochemical cycles.

39Moreover, the use of a highly efficient counter electrode further improves the functionality of the device, maintaining all three optical states over several electrochemical cycles. The improved reversibility of the different optical states displayed by the liquid device could be due to the counter electrode changing from a small Pt foil (1–2 cm2) in the three-electrode configuration, to the CeO2-based film (5 cm2). Moreover, the position of the counter electrode relative to the working electrode changes from one setup to the other: with three electrodes, the Pt foil is placed on the side of the sample to not cross the incident light beam (see Fig. 15a), while the CeO2-based films are placed directly in front of the MoWOx film at a close distance of 2–3 mm (Figs. 15b,c).

Figure 15: Picture of the three-electrode setup, comprising the working, counter, and reference electrodes (a) and of the two-electrode liquid (b) and solid-state setups (c).

40The combined effect of the position and size of the Pt counter electrode can lead to high current densities within the active layer, causing irreversible damage to the material—especially at its surface—and thereby degrading its plasmonic properties. Therefore, using a more appropriate counter electrode with a sufficiently large area for an efficient charge transfer in the system, prevents damage to the active layer and allows the intermediate state to occur even after a complete electrochemical cycle.

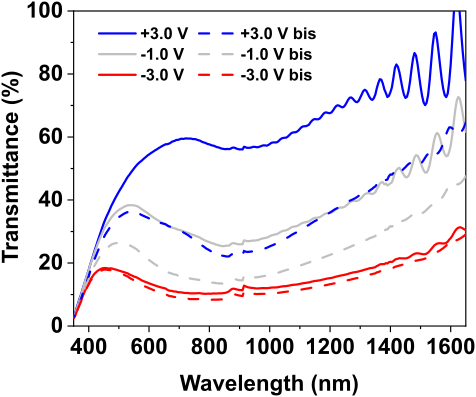

41Finally, solid-state devices were produced using a polymer gel electrolyte to bind the two electrodes together, instead of immersing them in an electrolyte solution. Using a LiTFSI-in-BmimTFSI gel electrolyte, the MoWOx working electrode and the CeO2-based counter electrode were assembled into a single unit, which solidified upon thermal curing of the gel. Here again, the device exhibited similar performances to the previously discussed cases, with the dual-band activity of MoWOx clearly displayed in the spectroelectrochemical spectra over multiple cycles (Fig. 16).

Figure 16: Transmittance spectra of the MoWOx/CeMo6 solid-state setup as a function of the applied potential, and repeated over three electrochemical cycles.

42All in all, these successful characterizations conceptualize the production of fully assembled solid-state devices, exploiting MoWOx dual band plasmonic formulations as active layers. The obtained results show good electrochromic results in the first coloration/bleaching cycle of both liquid and solid-state devices, and prove the interesting properties of the MoWOx formulation, highlighting its potential as a promising candidate for the future development of highly efficient smart windows towards increased energy savings in buildings.

8. Conclusions

43In summary, the work conducted on MoWOx at GREEnMat highlights the distinctive properties of this innovative formulation, and demonstrates its potential for application as a dual-band electrochromic material.

44Initial characterization of the powders revealed an interesting urchin-like particle morphology and a strong absorption covering both the VIS and NIR regions. With these promising morphology and optical properties, MoWOx was processed into thin films and its electrochromic performances investigated, successfully demonstrating the targeted dual-band modulation behavior. The active films presented three optical states: a peculiar initial warm state arising from the strong optical absorption of the material and limiting its maximal transmittance in the VIS range; an intermediate, NIR-preferential state; and a dark state once a sufficiently reducing potential is applied. However, reversibility assessment revealed that the intermediate state was lost already from the second electrochemical cycle.

45Finally, MoWOx films were combined with CeO2-based counter electrodes for the design of complete electrochromic devices. Liquid-electrolyte setups were first investigated, followed with the production of solid-state devices using a polymer gel electrolyte to assemble the electrodes as a single unit. Notably, these devices exhibited superior performance to standalone films, particularly respect to preserving the intermediate state after complete coloration into the dark state. Using a more appropriate Mo-doped CeO2 counter electrode (with a comparable size to that of the working electrode), the MoWOx active formulation was capable to maintain its three working states over multiple cycles of coloration/bleaching, in both liquid and solid-state setups.

46In conclusion, the results obtained in this study demonstrate show the promising properties of the MoWOx formulation, particularly with respect to its potential application as a dual-band electrochromic material. Future work looking into the peculiar optoelectronic behavior of this material should focus on further extending its optical range, to reach higher transmittance in the bleached/warm state, to better meet the requirements for commercial applications (at least 60 % VIS transmittance in the most oxidized state). In addition, more research is necessary to elucidate the origin of this unusual warm state and improve our control over this optical mode, which could significantly impact the adaptability of smart windows to external conditions, such as the weather and seasonal variations, ultimately leading to increased energy savings in buildings.

Acknowledgments

47This work was made possible through the support of the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (F.R.S.)–FNRS under the convention PDR T.0125.20 “PLASMON_EC”.

Further Information

Author’s ORCID identifier

480009-0000-2434-6960 (Florian Gillissen)

Conflicts of interest

49The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Bibliographie

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Final_energy_consumption_in_industry_-_detailed_statistics#Energy_products_used_in_the_industry_sector. Accessed: 14 April 2025.

[2] https://www.eia.gov/totalenergy/data/monthly. Accessed: 14 April 2025.

[3] Taguchi, T. (2007) Present status of energy saving technologies and future prospect in white LED lighting. IEEJ Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Engineering, 3(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/tee.20228.

[4] Cao, X., Dai, X., and Liu, J. (2016) Building energy-consumption status worldwide and the state-of-the-art technologies for zero-energy buildings during the past decade. Energy and Buildings, 128, 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.06.089.

[5] Stadler, M., Siddiqui, A., Marnay, C., Aki, H., and Lai, J. (2011) Control of greenhouse gas emissions by optimal DER technology investment and energy management in zero-net-energy buildings. European Transactions on Electrical Power, 21(2), 1291–1309. https://doi.org/10.1002/etep.418.

[6] Niachou, A., Papakonstantinou, K., Santamouris, M., Tsangrassoulis, A., and Mihalakakou, G. (2001) Analysis of the green roof thermal properties and investigation of its energy performance. Energy and Buildings, 33(7), 719–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-7788(01)00062-7.

[7] https://www.stainless-structurals.com/blog/a-trend-in-modern-architecture-more-glass. Accessed: 8 April 2025.

[8] https://ghi.co.za/industry-trends-the-use-of-glass-in-architecture/. Accessed: 8 April 2025.

[9] Wang, Y., Runnerstrom, E. L., and Milliron, D. J. (2016) Switchable materials for smart windows. Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, 7, 283–304. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-080615-034647.

[10] Austin, R. R. (1993). Solar control properties in low emissivity coatings. patent n∘ 5183700, 02/02/1993. https://patents.google.com/patent/US5183700.

[11] German, J. R. and Pfaff, G. L. Solar control low-emissivity coatings. patent n∘ 2630363, 12/01/2016.

[12] Granqvist, C. G., Lansåker, P. C., Mlyuka, N. R., Niklasson, G. A., and Avendaño, E. (2009) Progress in chromogenics: New results for electrochromic and thermochromic materials and devices. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 93(12), 2032–2039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2009.02.026.

[13] SageGlass (Saint-Gobain). https://www.sageglass.com/en-gb. Accessed: 10 April 2025.

[14] AGC Glass Europe. Discover Halio: AGC Glass Europe’s new interactive windows and walls. https://www.agc-glass.eu/en/news/press-release/discover-halio-agc-glass-europes-new-interactive-windows-and-walls. Accessed: 10 April 2025.

[15] Denayer, J., Aubry, P., Bister, G., Spronck, G., Colson, P., Vertruyen, B., Lardot, V., Cambier, F., Henrist, C., and Cloots, R. (2014) Improved coloration contrast and electrochromic efficiency of tungsten oxide films thanks to a surfactant-assisted ultrasonic spray pyrolysis process. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 130, 623–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2014.07.038.

[16] Mortimer, R. J. (2011) Electrochromic materials. Annual Review of Materials Research, 41, 241–268. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-matsci-062910-100344.

[17] Zhai, Y., Li, J., Shen, S., Zhu, Z., Mao, S., Xiao, X., Zhu, C., Tang, J., Lu, X., and Chen, J. (2022) Recent advances on dual-band electrochromic materials and devices. Advanced Functional Materials, 32(17), 100524. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202109848.

[18] Wang, Z., Wang, X., Cong, S., Geng, F., and Zhao, Z. (2020) Fusing electrochromic technology with other advanced technologies: A new roadmap for future development. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports, 140, 100524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mser.2019.100524.

[19] Wang, J., Zhang, L., Yu, L., Jiao, Z., Xie, H., Lou, X. W., and Wei Sun, X. (2014) A bi-functional device for self-powered electrochromic window and self-rechargeable transparent battery applications. Nature Communications, 5, 4921. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5921.

[20] Kraft, A. (2018) Electrochromism: a fascinating branch of electrochemistry. ChemTexts, 5, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40828-018-0076-x.

[21] Zhai, Y., Zhu, Z., Zhou, S., Zhu, C., and Dong, S. (2018) Recent advances in spectroelectrochemistry. Nanoscale, 10(7), 3089–3111. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7nr07803j.

[22] Chatzikyriakou, D., Maho, A., Cloots, R., and Henrist, C. (2017) Ultrasonic spray pyrolysis as a processing route for templated electrochromic tungsten oxide films. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 240, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.11.001.

[23] Castenmiller, C. J. J. (2004) Surface temperature of wooden window frames under influence of solar radiation. HERON, 49(4), 339–348. https://heronjournal.nl/49-4/3.html.

[24] Li, S., Zhou, Y., Zhong, K., Zhang, X., and Jin, X. (2013) Thermal analysis of PCM-filled glass windows in hot summer and cold winter area. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies, 11(2), 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijlct/ctt073.

[25] Arslan, M., Firat, Y. E., Tokgöz, S. R., and Peksoz, A. (2021) Fast electrochromic response and high coloration efficiency of Al-doped WO3 thin films for smart window applications. Ceramics International, 47(23), 32 570–32 578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.152.

[26] Yamashita, J. and Kurosawa, T. (1958) On electronic current in NiO. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, 5(1-2), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3697(58)90129-X.

[27] Sewell, G. L. (1958) Electrons in polar crystals. Philosophical Magazine, 3(36), 1361–1380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786435808233324.

[28] Holstein, T. (1959) Studies of polaron motion. Annals of Physics, 8(3), 343–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(59)90003-X.

[29] Landau, L. D. (1965) Electron motion in crystal lattices. In Collected Papers of L. D. Landau, edited by ter Haar, D., chapter 10, pages 67–68. Gordon and Breach, and Pergamon Press, New York (NY), and Oxford (UK). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-010586-4.50015-8. Originally published as “Über die Bewegung der Elektronen im Kristallgitter” Phys. Z. Sowjetunion 3:664, 1933.

[30] Tandon, B., Lu, H.-C., and Milliron, D. J. (2022) Dual-band electrochromism: Plasmonic and polaronic mechanisms. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 126(22), 9228–9238. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.2c02155.

[31] Tavares, P. F., Gaspar, A. R., Martins, A. G., and Frontini, F. (2014) Evaluation of electrochromic windows impact in the energy performance of buildings in Mediterranean climates. Energy Policy, 67, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.07.038.

[32] DeForest, N., Shehabi, A., Selkowitz, S., and Milliron, D. J. (2017) A comparative energy analysis of three electrochromic glazing technologies in commercial and residential buildings. Applied Energy, 192, 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.02.007.

[33] Runnerstrom, E. L., Llordés, A., Lounis, S. D., and Milliron, D. J. (2014) Nanostructured electrochromic smart windows: traditional materials and NIR-selective plasmonic nanocrystals. Chem. Commun., 50(73), 10 555–10 572. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4cc03109a.

[34] Agrawal, A., Cho, S. H., Zandi, O., Ghosh, S., Johns, R. W., and Milliron, D. J. (2018) Localized surface plasmon resonance in semiconductor nanocrystals. Chemical Reviews, 118(6), 3121–3207. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00613.

[35] Runnerstrom, E. L. (2016) Charge transport in metal oxide nanocrystal-based materials. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Berkeley. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1h2907bc.

[36] Llordes, A., Runnerstrom, E. L., Lounis, S. D., and Milliron, D. J. (2015) Plasmonic electrochromism of metal oxide nanocrystals. In Electrochromic Materials and Devices, edited by Mortimer, R. J., Rosseinsky, D. R., and Monk, P. M. S., chapter 13, pages 363–398. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim (DE). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527679850.ch13.

[37] Boschloo, G. and Fitzmaurice, D. (1999) Spectroelectrochemistry of highly doped nanostructured tin dioxide electrodes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 103(16), 3093–3098. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9835566.

[38] Lounis, S. D., Runnerstrom, E. L., Llordés, A., and Milliron, D. J. (2014) Defect chemistry and plasmon physics of colloidal metal oxide nanocrystals. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 5(9), 1564–1574. https://doi.org/10.1021/jz500440e.

[39] Garcia, G., Buonsanti, R., Runnerstrom, E. L., Mendelsberg, R. J., Llordes, A., Anders, A., Richardson, T. J., and Milliron, D. J. (2011) Dynamically modulating the surface plasmon resonance of doped semiconductor nanocrystals. Nano Letters, 11(10), 4415–4420. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl202597n.

[40] Garcia, G., Buonsanti, R., Llordes, A., Runnerstrom, E. L., Bergerud, A., and Milliron, D. J. (2013) Near-infrared spectrally selective plasmonic electrochromic thin films. Advanced Optical Materials, 1(3), 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201200051.

[41] Llordés, A., Garcia, G., Gazquez, J., and Milliron, D. J. (2013) Tunable near-infrared and visible-light transmittance in nanocrystal-in-glass composites. Nature, 500, 323–326. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12398.

[42] Kim, J., Ong, G. K., Wang, Y., LeBlanc, G., Williams, T. E., Mattox, T. M., Helms, B. A., and Milliron, D. J. (2015) Nanocomposite architecture for rapid, spectrally-selective electrochromic modulation of solar transmittance. Nano Letters, 15(8), 5574–5579. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02197.

[43] Zhang, S., Cao, S., Zhang, T., Yao, Q., Fisher, A., and Lee, J. Y. (2018) Monoclinic oxygen-deficient tungsten oxide nanowires for dynamic and independent control of near-infrared and visible light transmittance. Materials Horizons, 5(2), 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7mh01128h.

[44] Zhang, S., Cao, S., Zhang, T., Fisher, A., and Lee, J. Y. (2018) Al3+ intercalation/de-intercalation-enabled dual-band electrochromic smart windows with a high optical modulation, quick response and long cycle life. Energy & Environmental Science, 11(10), 2884–2892. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ee01718b.

[45] Zhang, S., Li, Y., Zhang, T., Cao, S., Yao, Q., Lin, H., Ye, H., Fisher, A., and Lee, J. Y. (2019) Dual-band electrochromic devices with a transparent conductive capacitive charge-balancing anode. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 11(51), 48 062–48 070. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b17678.

[46] Lu, H.-C., Ghosh, S., Katyal, N., Lakhanpal, V. S., Gearba-Dolocan, I. R., Henkelman, G., and Milliron, D. J. (2020) Synthesis and dual-mode electrochromism of anisotropic monoclinic Nb12O29 colloidal nanoplatelets. ACS Nano, 14(8), 10 068–10 082. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c03283.

[47] Dahlman, C. J., Tan, Y., Marcus, M. A., and Milliron, D. J. (2015) Spectroelectrochemical signatures of capacitive charging and ion insertion in doped anatase titania nanocrystals. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 137(28), 9160–9166. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b04933.

[48] Barawi, M., De Trizio, L., Giannuzzi, R., Veramonti, G., Manna, L., and Manca, M. (2017) Dual band electrochromic devices based on Nb-doped TiO2 nanocrystalline electrodes. ACS Nano, 11(4), 3576–3584. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.6b06664.

[49] Yin, H., Kuwahara, Y., Mori, K., Cheng, H., Wen, M., Huo, Y., and Yamashita, H. (2017) Localized surface plasmon resonances in plasmonic molybdenum tungsten oxide hybrid for visible-light-enhanced catalytic reaction. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 121(42), 23 531–23 540. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b08403.

[50] Yin, H., Kuwahara, Y., Mori, K., and Yamashita, H. (2018) Plasmonic metal/MoxW1−xO3−y for visible-light-enhanced H2 production from ammonia borane. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 6(23), 10 932–10 938. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ta03125h.

[51] Zhong, X., Sun, Y., Chen, X., Zhuang, G., Li, X., and Wang, J.-G. (2016) Mo doping induced more active sites in urchin-like W18O49 nanostructure with remarkably enhanced performance for hydrogen evolution reaction. Advanced Functional Materials, 26(32), 5778–5786. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201601732.

[52] Zhao, Y., Tang, Q., He, B., and Yang, P. (2017) Mo incorporated W18O49 nanofibers as robust electrocatalysts for high-efficiency hydrogen evolution. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 42(21), 14 534–14 546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.04.115.

[53] Wang, Q., Li, C., Xu, W., Zhao, X., Zhu, J., Jiang, H., Kang, L., and Zhao, Z. (2017) Effects of Mo-doping on microstructure and near-infrared shielding performance of hydrothermally prepared tungsten bronzes. Applied Surface Science, 399, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.12.022.

[54] Zhang, N., Jalil, A., Wu, D., Chen, S., Liu, Y., Gao, C., Ye, W., Qi, Z., Ju, H., Wang, C., Wu, X., Song, L., Zhu, J., and Xiong, Y. (2018) Refining defect states in W18O49 by Mo doping: A strategy for tuning N2 activation towards solar-driven nitrogen fixation. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 140(30), 9434–9443. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b02076.

[55] Spetter, D., Tahir, M. N., Hilgert, J., Khan, I., Qurashi, A., Lu, H., Weidner, T., and Tremel, W. (2018) Solvothermal synthesis of molybdenum–tungsten oxides and their application for photoelectrochemical water splitting. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 6(10), 12 641–12 649. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01370.

[56] Yang, M., Huo, R., Shen, H., Xia, Q., Qiu, J., Robertson, A. W., Li, X., and Sun, Z. (2020) Metal-tuned W18O49 for efficient electrocatalytic N2 reduction. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 8(7), 2957–2963. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b07526.

[57] Li, P., Zhu, L., Ma, C., Zhang, L., Guo, L., Liu, Y., Ma, H., and Zhao, B. (2020) Plasmonic molybdenum tungsten oxide hybrid with surface-enhanced raman scattering comparable to that of noble metals. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 12(16), 19 153–19 160. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c00220.

[58] Xiong, J., Li, J., Huang, H., Zhang, M., Zhu, W., Zhou, J., Li, H., and Di, J. (2022) Electronic state tuning over Mo-doped W18O49 ultrathin nanowires with enhanced molecular oxygen activation for desulfurization. Separation and Purification Technology, 294, 121167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2022.121167.

[59] Gillissen, F., Lobet, M., Dewalque, J., Colson, P., Spronck, G., Gouttebaron, R., Duttine, M., Faceira, B., Rougier, A., Henrard, L., Cloots, R., and Maho, A. (2025) Mixed molybdenum–tungsten oxide as dual-band, VIS–NIR selective electrochromic material. Advanced Optical Materials, 13(7), 2401995. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202401995.

[60] Lobet, M., Gillissen, F., De Moor, N., Dewalque, J., Colson, P., Cloots, R., Maho, A., and Henrard, L. (2025) Plasmonic properties of doped metal oxides investigated through the Kubelka–Munk formalism. ACS Applied Optical Materials, 3(2), 296–304. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaom.4c00432.

[61] Gillissen, F. (2024) Innovative Electrode Materials for Dual Band Visible–Near Infrared Electrochromic Smart Windows. Ph.D. thesis, Université de Liège, Liège (BE). https://hdl.handle.net/2268/325666.

[62] Manthiram, K. and Alivisatos, A. P. (2012) Tunable localized surface plasmon resonances in tungsten oxide nanocrystals. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 134(9), 3995–3998. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja211363w.

[63] Salje, E. and Güttler, B. (1984) Anderson transition and intermediate polaron formation in WO3−x transport properties and optical absorption. Philosophical Magazine B, 50(5), 607–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642818408238882.

[64] Li, H., Chen, J., Cui, M., Cai, G., Eh, A. L.-S., Lee, P. S., Wang, H., Zhang, Q., and Li, Y. (2016) Spray coated ultrathin films from aqueous tungsten molybdenum oxide nanoparticle ink for high contrast electrochromic applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 4(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5tc02802g.

[65] Zhou, D., Shi, F., Xie, D., Wang, D. H., Xia, X. H., Wang, X. L., Gu, C. D., and Tu, J. P. (2016) Bi-functional Mo-doped WO3 nanowire array electrochromism-plus electrochemical energy storage. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 465, 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2015.11.068.

[66] Li, H., Li, J., Hou, C., Ho, D., Zhang, Q., Li, Y., and Wang, H. (2017) Solution-processed porous tungsten molybdenum oxide electrodes for energy storage smart windows. Advanced Materials Technologies, 2(8), 1700047. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201700047.

[67] Li, H., McRae, L., Firby, C. J., Al-Hussein, M., and Elezzabi, A. Y. (2018) Nanohybridization of molybdenum oxide with tungsten molybdenum oxide nanowires for solution-processed fully reversible switching of energy storing smart windows. Nano Energy, 47, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.02.043.

[68] Li, H., McRae, L., and Elezzabi, A. Y. (2018) Solution-processed interfacial PEDOT:PSS assembly into porous tungsten molybdenum oxide nanocomposite films for electrochromic applications. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 10(12), 10 520–10 527. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b18310.

[69] Xie, S., Bi, Z., Chen, Y., He, X., Guo, X., Gao, X., and Li, X. (2018) Electrodeposited Mo-doped WO3 film with large optical modulation and high areal capacitance toward electrochromic energy–storage applications. Applied Surface Science, 459, 774–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.08.045.

[70] Wang, B., Man, W., Yu, H., Li, Y., and Zheng, F. (2018) Fabrication of Mo-doped WO3 nanorod arrays on FTO substrate with enhanced electrochromic properties. Materials, 11(9), 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11091627.

[71] Kumar, A., Prajapati, C. S., and Sahay, P. P. (2019) Modification in the microstructural and electrochromic properties of spray-pyrolysed WO3 thin films upon Mo doping. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology, 90(2), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10971-019-04960-1.

[72] Li, W., Zhang, J., Zheng, Y., and Cui, Y. (2022) High performance electrochromic energy storage devices based on Mo-doped crystalline/amorphous WO3 core-shell structures. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 235, 111488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2021.111488.

[73] Gillissen, F., Colson, P., Spronck, G., Maho, A., Cloots, R., and Dewalque, J. (2026) Development of molybdenum doped cerium oxide passive counter electrodes by surfactant-assisted ultrasonic spray pyrolysis. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 296, 114060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2025.114060.

Om dit artikel te citeren:

Over : Florian Gillissen

University of Liège, Quartier Agora - B6a, Allée du Six Août 13, B–4000 Liège, Belgium

email: fgillissen@uliege.be