Would you harm a fly?

An introduction to Drosophila suzukii and alternative methods for controlling this invasive pest

Résumé

La Révolution Verte a fortement modifié les méthodes de production agricoles. L’agriculture est devenue plus spécialisée et intensive, et l’usage des produits phytopharmaceutiques, parmi lesquels les insecticides, s’est intensifié. Ceux-ci sont cependant néfastes pour l’environnement et la santé humaine. En parallèle, la mondialisation a conduit à l’introduction d’espèces exotiques envahissantes (dites invasives), dont l’établissement en Europe a été facilité par l’abondance en ressources nutritives et l’absence d’ennemis naturels. Ces constats sont particulièrement vrais avec Drosophila suzukii. Cette mouche est aujourd’hui considérée comme le principal ravageur des fruits dans le monde. Ainsi, il devient urgent de trouver des méthodes de lutte alternatives aux insecticides pour contrer les dégâts économiques causés par ce nouveau ravageur. Cependant, le développement d’une approche par lutte intégrée requiert une excellente compréhension de la biologie et de l’écologie de l’espèce. Dans ce document, nous présentons dans un premier temps l’état des connaissances sur le cycle de vie, les plantes hôtes et la phénologie de D. suzukii. La répartition géographique actuelle et l’historique d’invasion de ce ravageur sont détaillés, avant d’estimer l’ampleur des pertes économiques causées. Dans une seconde partie, les méthodes alternatives de lutte connues contre D. suzukii sont répertoriées : pratiques culturales, traitements post-récoltes, lâchés d’insectes stériles, utilisation d’ennemis naturels et manipulation comportementale (visuelle et olfactive). Finalement, dans une troisième partie, nous verrons comment ces moyens de lutte peuvent être combinés afin d’améliorer le contrôle de ce ravageur.

Abstract

The Green Revolution has greatly changed agricultural production methods. Agriculture has become more specialized and intensive, and the use of phytopharmaceutical products, including insecticides, has intensified. However, these are harmful to the environment and human health. At the same time, globalization has led to the introduction of alien species (called invasive), whose establishment in Europe has been facilitated by the abundance of nutritive resources and the absence of natural enemies. These observations are particularly true with Drosophila suzukii. This fly is now considered as the main fruit pest in the world. Thus, it is becoming urgent to find alternative control methods to insecticides to counter the economic damage caused by this new pest. However, the development of an integrated pest management approach requires an excellent understanding of the biology and ecology of the species. In this paper, we first present the state of knowledge on the life cycle, host plants and phenology of D. suzukii. The current geographical distribution and the history of invasion of this pest are detailed, before estimating the extent of the economic losses caused. In a second part, the known alternative control methods against D. suzukii are listed: cultural practices, post-harvest treatments, sterile insect releases, uses of natural enemies and behavioral manipulations (visual and olfactory). Finally, in a third part, we will see how these methods can be combined to improve the control of this pest.

Manuscript received on May 29, 2022 and accepted on October 3, 2022

This article is distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC-BY 4.0

Cet article a reçu un des deux Prix Annuels 2022 de la Société Royale des Sciences de Liège. This paper was awarded one of the two Annual Prizes 2022 of the Société Royale des Sciences de Liège,

1. Introduction

1After the Second World War, the world population growth has created the need for a marked increase in food production and food security (self-sufficiency). The Green Revolution of the 1960s met this need by doubling the production of food worldwide (Mann, 1999). This was achieved partially through the use of insecticides to protect crops from pests (Baulcombe et al., 2009; Mahmood et al., 2016). The intensification of the use of these chemical products has rapidly brought to light many problems related to human health. Pesticide residues are found in food, leading to cancers and diseases (about 3 million cases of pesticide poisoning per year) (Kim et al., 2017; Nasreddine & Parent-Massin, 2002). Pesticides also have a negative impact on the environment due to their low specificity and high dispersal ability. They decrease biodiversity by killing non-target organisms and degrading their habitats (Pisa et al., 2014; Robinson & Sutherland, 2002; Schwarzenbach et al., 2010). Moreover, the law pushes to reduce the use of insecticides (Epstein et al., 2021, 2022). Finally, beyond the adverse effects on human health and the environment, pesticide use is very costly for farmers (up to around €6.06 billion per year worldwide in total) (Alavanja et al., 2004; Mostafalou & Abdollahi, 2017).

2The Green Revolution has also transformed the structure of agriculture by creating monocultures. Agriculture has become more specialized and intensive, driven by new crop breeding for higher yield, increase in mechanization and in the area of land under cultivation (Baulcombe et al., 2009). At the same time, the processes of free exchange (commercial and human) have intensified. Globalization facilitates the introduction and establishment of invasive species (Daane et al., 2018; Meyerson & Mooney, 2007; Pyšek & Richardson, 2010). These pests establish themselves in new areas, where no natural enemies are present to limit their propagation and where resources are unlimited for them due to monocultures (Altieri, 2020). Thus, the intensification of monocultures and globalization allows the emergence of pests that decrease yields (Martinet & Meiss, 2020). With a further increase in human population expected to reach about 9 billion people by 2050, current projections indicate that food production will have to double over the two coming decades (Baulcombe et al., 2009). We therefore face a three-fold challenge: how to increase production while changing our means of production, mostly by reducing chemical inputs, and controlling native and invasive pests?

3This challenge is particularly true with the vinegar fly D. suzukii. Also called the Spotted-Wing Drosophila (SWD), this pest is now present on almost the entire globe and its expansion does not stop. It develops inside soft-skinned fruits, causing damages and therefore important economic losses (Little et al., 2017). Although many ecofriendly alternatives are being developed, insecticide (mainly spinosad) is the most common method to control this pest (Bruck et al., 2011; Van Timmeren & Isaacs, 2013). In addition to adverse effects of chemical products, SWD is physiologically and behaviorally resistant to many chemical products. Indeed, when an insecticide is used, D. suzukii takes refuge in wild plants and then recolonizes crops (Kenis et al., 2016; Tonina, Mori, et al., 2018). Moreover, the required dose of insecticide to manage the fly population is increasing, as demonstrated recently in California (Gress & Zalom, 2019; Van Timmeren et al., 2018). Wholesalers and retailers apply a zero-tolerance policy and reject the fruits when they detect infestation. This pushes the growers to use chemical control, taking the risk of increasing the resistance and reducing the efficacy of the few chemical products available (Asplen et al., 2015; Tait et al., 2021).

4Integrated Pest Management (IPM) could optimize control of D. suzukii in an environmentally friendly and economical manner (Ehler, 2006). IPM includes efficient monitoring of populations, modeling their demography and distribution, preventing new introductions and the use of alternative methods to pesticides (Cini et al., 2012). Nevertheless, a good knowledge of the pest is a silver bullet for a successful IPM (Vreysen et al., 2007). Thus, we describe the biology and ecology of D. suzukii, its invasion and economic impacts. Then, we report the different alternative methods. Finally, we discuss how to combine these methods to work towards a global IPM.

2. Drosophila suzukii

2.1. Biology and ecology

2.1.1. Morphology and life cycle

5Drosophila suzukii (Matsumara 1931) is a fly species of the Diptera order and the Drosophilidae family. It has a size of 2 to 3 mm, red eggs, yellow-brown abdomen and thorax with black streaks on the abdomen (Asplen et al., 2015; Walsh et al., 2011). Females are slightly larger than the males (Calabria et al., 2012). The first are recognized by serrated saw-like ovipositor (Hauser, 2011), while the males are differentiated from those of other species by their black spot at the end of each wing (Walsh et al., 2011). However, immature stages of SWD (egg, larvae and pupal) are indistinguishable from other Drosophila species (Okada, 1968).

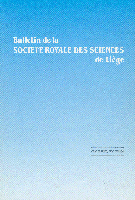

6Mating can occur on the first day of adult life and female lay its eggs in the fruit the next day (Cini et al., 2012) but mating activity strongly increases the first 3 days (Revadi et al., 2015). Females lay during all its life, which represents an average of 380 eggs per female, which is considered as a rather high fecundity (Asplen et al., 2015; Mitsui et al., 2010). Generally, SWD life cycle lasts between 13 to 18 days but is impacted by temperature, and adults live between 3 to 9 weeks (Cini et al., 2012; Weydert & Mandrin, 2013) (Figure 1). Thus, up to 15 generations per year are possible (Cini et al., 2012). Therefore, the short generation time and the high fecundity of this pest lead to exponential population growth, explaining the very high infestation pressure during fruit ripening period (Asplen et al., 2015).

Figure 1.

Life cycle of Drosophila suzukii with direct and indirect damages. L1, L2 and L3 correspond respectively to the larval stage 1, 2 and 3. Made with Biorender ®

2.1.2. Damages and hosts

7Thanks to its ovipositor, SWD lays its eggs in ripe or ripening soft-skinned fruits (Mitsui et al., 2006; Walsh et al., 2011). This oviposition causes direct damage, via the consumption of the fruit by the larva. Oviposition also causes indirect damages: the scar left during the oviposition favors bacterial and fungal infections (Cini et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2011) (Figure 1). In both cases, fruits rot and are unmarketable. D. suzukii has a wide host range of over 150 species (cultivated and wild plants) (Lee et al., 2015; Stockton et al., 2019; Thistlewood et al., 2019). Principal hosts are cultivated plants such as strawberries, raspberries and blueberries (Bellamy et al., 2013). Wild hosts are used as refuges during winter and promote dispersion (Elsensohn & Loeb, 2018). Indeed, wild berries at the margins of fields are oviposition sites for D. suzukii, promoting its dispersal during the ripening period. In addition, forests also contain non-cultivated hosts that provide overwintering habitat for adult D. suzukii (Buck et al., 2022; Rossi-Stacconi et al., 2016; Shearer et al., 2016; Stockton et al., 2019).

2.1.3. Phenology

8Drosophila suzukii is considered as a species with a high thermal tolerance (hot and cold) (Asplen et al., 2015; Cini et al., 2012). Its ability to resist cold temperatures allows it to survive winter in temperate climates (Rossi-Stacconi et al., 2016; Shearer et al., 2016; Stockton et al., 2019). Indeed, adult females change their phenotype following abiotic changes of the environment which gives them a greater cold tolerance (Shearer et al., 2016; Stockton et al., 2018). However, the mechanisms related to this seasonal polyphenism are still poorly understood (Lee et al., 2011; Panel et al., 2018). Immature stages (egg and larvae) also have similar resistance abilities which allow them to survive transportation between continents via containers (Rossi-Stacconi et al., 2016; Shearer et al., 2016; Stockton et al., 2019).

9Although SWD adults are mainly active from spring to fall, they represent only 10% of the fly population, which is made for 90% of immature stages (eggs, larvae, pupae) (Grassi et al., 2018; Wiman et al., 2014). SWD populations vary according to biotic and abiotic factors but are at their maximum in autumn, decline during winter and then increase again with the arrival of spring (Dos Santos et al., 2017; Little et al., 2020). Also, this pest is more active at dawn and at dusk (Hamby et al., 2013; Tait et al., 2020). D. suzukii has a dispersal ability linked to its physiological needs and to abiotic factors (temperature, food availability, humidity...etc.) (Tait et al., 2021). In early spring, SWD uses wild host plants to lay eggs. As the population increases, it moves from crop to crop finding refuge in wild plants (Klick et al., 2016; Leach et al., 2016; Tait et al., 2020). In summer, D. suzukii, thanks to its ability to disperse over long distances, colonizes crops at higher altitudes (Briem et al., 2017; Kenis et al., 2016). At the end of the summer, this pest pullulates at lower altitudes, continuing to move from crop to crop and finally finding refuge in uncultivated plants where it creates its overwintering phenotype to spend the winter (Tait et al., 2021).

2.2. Distribution and invasion

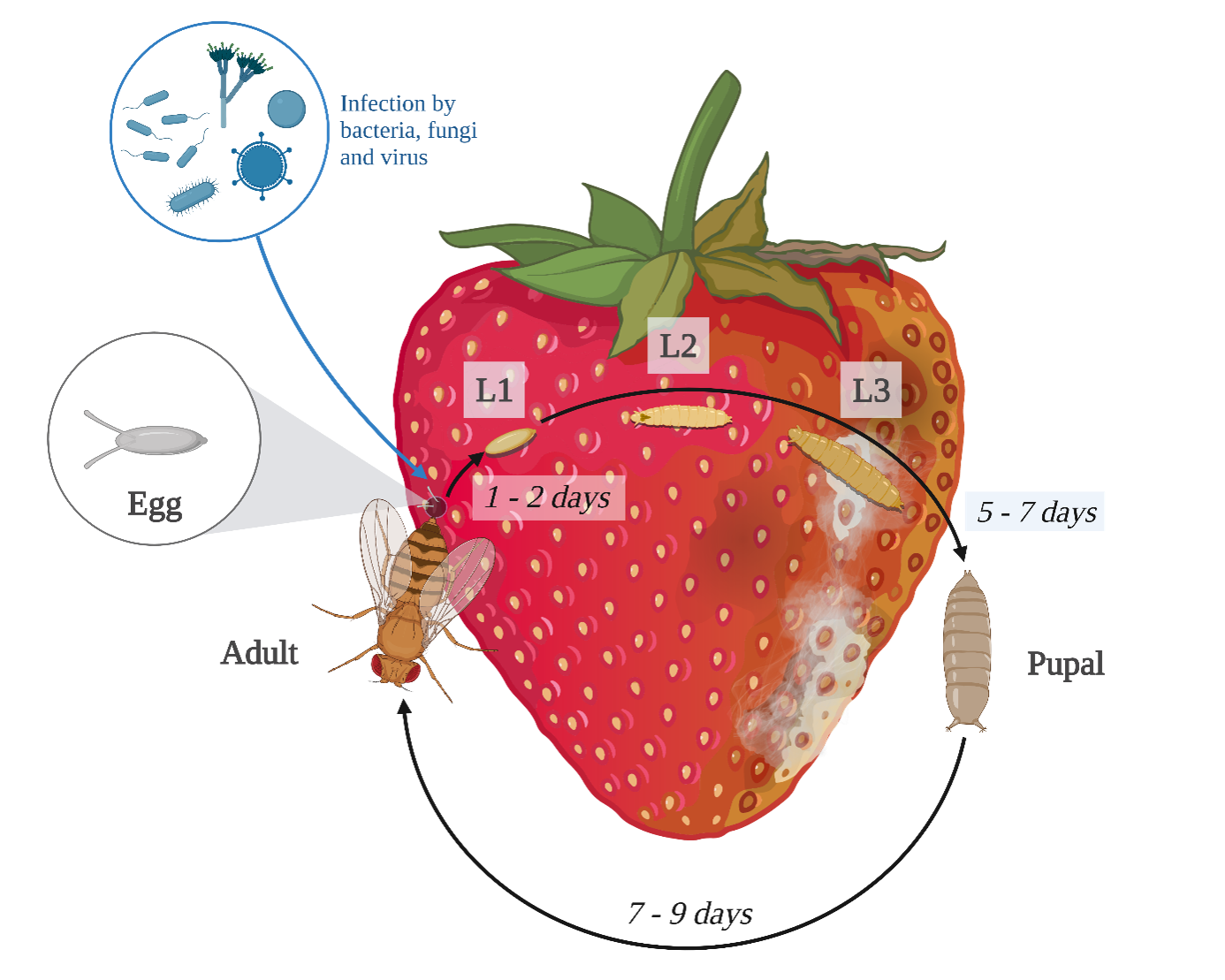

10The first records of SWD are in 1916 in Japan. From the 1930s, the infestations in cherry production were found to be common (Lee et al., 2011). In 1949, its presence was confirmed in Korea and China (Tan, 1949). Although its exact country of origin is not certain, it is however clear that it is native from East and Southeast Asia (Briem et al., 2017) (Figure 2).

11The presence of D. suzukii outside its native region was then first confirmed in the 1980s in Hawaii. In 2008, SWD was reported in California (USA), Spain (Europe) and Italy (Europe) and spread across Europe and North America in the following years (Cini et al., 2012; Hauser, 2011). In 2013, this pest was detected in South America (Andreazza et al., 2017; Deprá et al., 2014) and in 2017 in Africa (Boughdad et al., 2021; Hassani et al., 2020). Based on genetic analyses, three native populations would be at the origin of the global invasion (Fraimout et al., 2017). Recent modelling research suggests that the invasion of this pest will continue, particularly in Africa and Australia (Boughdad et al., 2021; Dos Santos et al., 2017) (Figure 2). Thus, D. suzukii has been able to adapt to very diverse regions and landscapes (Asplen et al., 2015).

12This global and rapid spread is partly due to the biology of this pest: short development time, high fertility and wide host-range, important thermal resistance, long-distance dispersal. But the transport of infected fruits likely is the main driver (Lewald et al., 2021; Westphal et al., 2008).

Figure 2.

Worldwide invasion scenario of D. suzukii. The native range is in dark grey, and the invasive range is in light-grey (Lewald et al., 2021; Westphal et al., 2008). The circles represent the sampling sites followed by the date of the first year when D. suzukii was observed. The colors for the sample sites and arrows correspond to the different genetic groups. The arrows indicate the most probable invasion pathways (Fraimout et al., 2017). Adapted from Fraimout et al 2017 with Biorender ®

2.3. Economic impact

13The economic impact of D. suzukii is hardly estimable. Indeed, the yield losses depend on the type of crops and regions (Tait et al., 2021). However, the main hosts are crops with high added value (strawberries and raspberries), leading to very important economic losses (De Ros et al., 2013). Only one year after its arrival in the USA, SWD’s damages were estimated at 20% to 80% of yield loss in three states (California, Oregon and Washington) on five main crops (strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, blackberries and cherries), for an estimated loss of 500 million USD (Bolda et al., 2010; Goodhue et al., 2011). In 2017, raspberry yield losses were estimated at 2 to 100% in Minnesota (USA) (DiGiacomo et al., 2019). The findings are the same in Europe with damage up to 100% on strawberries, cranberries and cherries, representing 3 million € of economic losses in 2011 (Asplen et al., 2015; De Ros et al., 2013; Weydert & Mandrin, 2013). More recently, the total losses linked to D. suzukii have been estimated at more than 800.000 € in one year in the province of Trento (Italy) while growers used control methods (De Ros et al., 2021). These examples do not include the increase in management costs for growers. However, this parameter is essential for a good estimation, since all control methods do not have the same effectiveness and cost (De Ros et al., 2015; Farnsworth et al., 2017; Yeh et al., 2020).

3. Alternative methods against D. suzukii

3.1. Cultural management

14The literature highlights several cultural practices that have a positive impact on D. suzukii control.

15Humidity influences survival, fecundity and development of D. suzukii (Fanning et al., 2018; Kirk Green et al., 2019). Drip irrigation, in particular, reduces the relative humidity and therefore the emergence of the pest (Rendon & Walton, 2019).

16Regular pruning of cultivated plants helps to modify the habitat and egg-laying sites of the pest. Indeed, the density of the leaves increases the activity of the adults and their reproduction. Thus, crops with little foliage experience reduced infestation by D. suzukii (Diepenbrock & Burrack, 2017; Schöneberg et al., 2021).

17Managing wild hosts, especially those in the proximity of crops, is essential to control this pest (Leach et al., 2019). Several wild plants species serve as refuges for SWD and are potential sources of infestation, including seedling cherries and Himalayan blackberries (Leach et al., 2019; Tait et al., 2020).

18Frequent harvesting of fruit reduces SWD infestation (Walsh et al., 2011). Moreover, destruction of overripe fruit prevents the spread of rot, bacteria or pests (Leach et al., 2016, 2018).

19Crops can be protected by nets (mesh size 0.98 mm), which act as a physical barrier to limit infestation (Cini et al., 2012; Cormier et al., 2015; Leach et al., 2016). This technique has been effective on raspberry and grape crops (Ebbenga et al., 2019; Rogers et al., 2016). However, the cost of netting is high and it also hinders beneficial insects from entering the crop (Schöneberg et al., 2021).

20 Finally, some varieties are less attractive to the pest and can result in lower infestation. The Müller-Thurgau and Pinot Blanc grape varieties are less susceptible to D. suzukii attack than the Pinot Noir variety (Weißinger et al., 2019).

3.2. Postharvest control

21Exposing fruits to cold (0.5, 1.1, 3.9 and 5.0 °C) for 24 to 72 hours after harvest reduces adult emergence (Kraft et al., 2020; Saeed et al., 2019).

22The irradiation (with X-ray) of fruits also allows to decrease the emergence of adults. Although the X-ray doses are different according to the developmental stages (40 Gy for the first and second larval stage and 80 Gy for the pupal stage), a minimum dose of 80 Gy is recommended (Follett et al., 2014; Kim & Park, 2016). A higher dose (150 Gy), on the immature stages of SWD present in the fruits, causes sterility of the adults and thus reduces their infestation pressure (Kim & Park, 2016).

3.3. Sterile insect release

23This technique consists of breeding the pest in large numbers, sterilizing it with ionizing radiation (gamma or X-rays), and releasing these sterile insects above the infested crops (Lanouette et al., 2017). The sterile insects will then mate with the non-sterile ones and produce non-viable eggs, leading to a significant decrease in the number of pests. Usually, sterilization is done on males (Knipling, 1979). This means of control is specific to the target pest, therefore respectful of the environment, and has no effect on humans. Moreover, it can be used in difficult to access areas (Dyck et al., 2005).

24SWD females are completely sterile with a dose of 50 Gy (Lanouette et al., 2017) or 75 Gy while 200 Gy is required to sterilize males (Krüger et al., 2018). This dose can be decreased if the adults are infected with Wolbachia bacteria (Nikolouli et al., 2020). Recently, releases of sterile males suppressed the wild female SWD population by up to 91% (Homem et al., 2022). However, that did not stop the females from damaging the fruits via oviposition allowing the infection of the fruit by bacteria or fungi (Cini et al., 2012; Lanouette et al., 2017). Moreover, the physiological characteristics of the pest (high fecundity, short generation time, ability to migrate) could very quickly eliminate sterile individuals from the population (Nikolouli et al., 2018).

3.4. Natural ennemies

25The use of natural enemies (macro- or micro-organisms), called biological control, allows to reduce the density of the pest population (Gurr & Wratten, 1999). Biological control can have three approaches. The first is the introduction and the establishment of natural enemies from the pest's native range (classical biological control) (Harris, 1991). Another approach, called augmentative biological control, consists of a release of native natural enemies to help them build larger populations (Van Lenteren & Bueno, 2003). Finally, conservation biological control tends to modify or preserve natural environments in order to increase the number of local natural enemies (Gurr et al., 2016).

3.4.1. Macro-organisms

3.4.1.1. Predators

26The predators of SWD are very diverse: earwigs, spiders, ants, carabids, true bugs but also birds and mammals (Lee et al., 2019). Although predators can attack adults, the main cases of predation are on the immature stages (eggs, larvae, pupae) (Lee et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020).

27Pupae on the soil surface undergo a higher predation rate (80% to 100 %) than those remaining in the fruit (61% to 91%) (Ballman et al., 2017; Woltz & Lee, 2017). However, the results are highly variable ranging from 1% (Kamiyama et al., 2019) to 100 % (Ballman et al., 2017; Woltz & Lee, 2017). Larvae predation is less effective with a maximum rate of 49% in blueberry crops.

28Immature stages are hidden in the fruit (except when the pupal fall to the ground), making it difficult for SWD predators to find prey (Lee et al., 2019). Moreover, the use of SWD predators, in biological control by augmentation, represents a very significant cost. However, predators (crickets, spiders, carabids, earwigs and ants) of SWD are very abundant in organic crops (Ballman et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2019; Woltz et al., 2017).

3.4.1.2. Parasitoids

29A parasitoid is an insect that lays its eggs in another organism, using them as a host. The parasitoid uses the nutrients of its host to develop and emerge later. The parasitoid will systematically kill the host in which it has developed (Lee et al., 2019). SWD parasitoids can attack larvae or pupae.

30The two main parasitoids of pupae are Trichopria drosophilae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) and Pachycrepoideus vindemia (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) (Rossi-Stacconi et al., 2015). However, they do not seem to be very effective (Mazzetto, Marchetti, et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2015). Indeed, although T. drosophilae has a preference for SWD pupae (Woltering et al., 2019), releases showed only a 34% reduction in infested fruit (Rossi-Stacconi et al., 2019). Release of P. vindemmiae have also shown mixed results (Hogg et al., 2022). However, both parasitoids show a potential for rapid adaptive evolution by increasing, after only 3 generations, their developmental success from 88 to 259% (Jarrett et al., 2022). Although they are the most widely used and effective, pupal parasitoids intervene after damage is already caused by D. suzukii.

31Larval parasitoids, originating from the same region as SWD, seem to be very effective against D. suzukii (Giorgini et al., 2019; Girod et al., 2018; Mitsui et al., 2007). The main species are Leptopilina japonica (Hymenoptera: Figitidae), Asobara japonica (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and Ganapsis brasiliensis (Hymenoptera: Figitidae) which had a parasite rate on SWD from 47.8% (Giorgini et al., 2019) to 75.1% (Girod et al., 2018). Concerning European larval parasitoids, three species were tested: Asobara tabida (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), Leptopilina heterotoma and Leptopilina boulardi (Hymenoptera Eucoilidae). A. tabida is not able to parasitize D. suzukii and both species of Leptopilina parasitize but without causing the death of the larva. Indeed, the immune system of the larvae allows them to fight against these parasitoids. These results suggest that host change is difficult for European specialist parasitoids (Chabert et al., 2012).

32The control of SWD with parasitoids could be achieved by introducing Asian larval parasitoids (L. japonica and A. japonica) (classical biological control) but also by releasing European pupal parasitoids (T. drosophilae and P. vindemmiae) (augmentative biological control).

3.4.1.3. Competitors

33A competitor will not kill the pest but will use the resources (egg-laying site or food) and thus limit the impact of the pest. Drosophila melanogaster and D. suzukii use the same egg-laying sites. Indeed, in laboratory, both species lay eggs in fruits that have already been parasitized by the other (Dancau et al., 2017; Shaw et al., 2018). Competition mechanisms are effective because D. melanogaster reduce the number of SWDs (Dancau et al., 2017). Drosophila melanogaster cannot have an impact on the marketed fruits because it lays its eggs in rotten fruits (Gao et al., 2018). However, at the end of the season, when SWD uses rotten fruits (Stemberger, 2016), D. melanogaster can interfere and reduce SWD populations before winter (Lee et al., 2019).

3.4.2. Micro-organisms

3.4.2.1. Virus

34Five viruses are lethal for SWD with an injection in the thorax: Drosophila A virus, La Jolla virus, Drosophila C virus, Cricket paralysis virus and Flock house virus. 100% of adults die after 17 to 19 days (Carrau et al., 2018; Lee & Vilcinskas, 2017). However, lethality can be greatly reduced if the adults are in symbiosis with the Wolbachia bacteria. Indeed, the lethality reaches 100% without its presence and 0% when it is present with the Drosophila C virus and Flock house virus (Cattel et al., 2016). This finding compromises the search for viruses against D. suzukii because 17% of the adults in North America and 46% in Europe are in symbiosis with Wolbachia bacteria (Cattel et al., 2016; Hamm et al., 2014).

3.4.2.2. Nematodes

35Many entomopathogenic nematodes (EPN), at the juvenile infectious stage, kills up to 69% of larvae (Cuthbertson & Audsley, 2016; Garriga et al., 2018; Renkema & Cuthbertson, 2018; Woltz et al., 2015). EPN are less effective on the pupae (Ibouh et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019) because they have difficulties to penetrate pupae (Garriga et al., 2018; Hübner et al., 2017). The most effective nematode species currently is Oscheius onirici which kills up to 78.2% of SWD larvae (Foye et al., 2020). The dose of nematode applied may partly explain the differences of efficacy in results (Hübner et al., 2017; Woltz et al., 2015). Furthermore, nematodes need a humid environment and are therefore mainly used against soil pests. Field trials are needed to evaluate their efficacy against SWD (Labaude & Griffin, 2018).

3.4.2.3. Bacteria

36The most commonly used bacteria for pest control is Bacillus thuringiensis (Biganski et al., 2018; Lacey et al., 2015). Five serovars are very lethal against SWD larvae, killing between 75 to 100% of the individuals. However, this bacterium cannot naturally come into contact with the larvae because it does not reach the internal part of the fruit (Biganski et al., 2020; Cahenzli et al., 2018; Cossentine et al., 2016). So far bacteria are not an option for D. suzukii management.

3.4.2.4. Fungi

37Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) are very effective natural pathogens against flies (Lacey et al., 2015). Six products containing EPF have a mortality rate ranging from 0% to 100% against SWD (Alnajjar et al., 2017; Cahenzli et al., 2018; Cossentine et al., 2016; Cuthbertson et al., 2014; Gargani et al., 2013; Rhodes et al., 2018; Woltz et al., 2015). These results are difficult to compare because the methods of infection vary considerably. The findings are the same with EPFs strains from universities (Alnajjar et al., 2017; Naranjo-Lázaro et al., 2014; Yousef et al., 2018). Laboratory tests must consider the reality of the field for the selection of effective EPF strains.

3.5. Behavioral manipulation

38Behavioral manipulation consists in disrupting the communication (olfactory, visual and vibratory) of the pest in order to limit its damage on the crops (Foster & Harris, 1997). Currently, behavioral manipulation on D. suzukii focuses primarily on mass trapping. It consists of using attractive signals to attract the pest into a trap from which they cannot escape and where they die (Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2009). D. suzukii uses visual signals to orient itself at long distance and olfactory stimuli at short distance (Cha et al., 2012; Little et al., 2019). Although several commercial products exist for the capture of D. suzukii, their efficacy and selectivity are highly variable depending on the crop and the time of the season (Brilinger et al., 2021; Larson et al., 2021; Whitener et al., 2022).

3.5.1. Visual

39Color and shape are strong stimuli for D. suzukii (Renkema et al., 2014; Rice et al., 2016). SWD has a high sensitivity for short wave colors (380 nm to 570 nm) (Little et al., 2019). Although the red and black objects are very attractive for SWD (Bolton et al., 2021; Kirkpatrick et al., 2016; Little et al., 2019), the contrast between the foreground and background colors would be more important (Kirkpatrick et al., 2016; Little et al., 2019). This is because its hosts are red fruits on dark foliage (green) (Kirkpatrick et al., 2016; Little et al., 2019).

3.5.2. Olfactive

40Semiochemicals are odorant molecules that allow living beings to adapt their behavior.

41They are divided into several categories (Table 1).

Table 1. The different categories of semiochemicals with their effects on the emitter and receiver; + when the effect is beneficial and - when the effect is negative

|

Semiochemicals |

Type of communication |

Effect on emitter |

Effect on receiver |

Example |

|

|

Pheromone |

Intraspecific |

+ |

+ |

Mate finding Alarm Aggregation |

|

|

Allelochemical |

Allomone |

Interspecific |

+ |

- |

Defense |

|

Kairomone |

- |

+ |

Predation |

||

|

Synomone |

+ |

+ |

Pollination |

||

3.5.2.1. Attractants

42Pheromones are very effective in behavioral manipulation. When they are sexual or aggregation, they allow to attract the pest. However, D. suzukii has lost the ability to produce the pheromone (cis-11-octadecenyl acetate) which is present in the melanogaster group (Dekker et al., 2015). However, SWD's neural system has retained the ability to perceive and react to this pheromone (Dekker et al., 2015). Thus, the search for attractive kairomone has been strongly developed (Cloonan et al., 2018).

43The main attractants for D. suzukii are apple cider vinegar (Burrack et al., 2015; Hampton et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2017; Iglesias et al., 2014; Jaffe et al., 2018; Landolt, Adams, Davis, et al., 2012; Lasa et al., 2020; Toledo-Hernández et al., 2021; Tonina, Grassi, et al., 2018), wine and vinegar blend (Cha et al., 2014; Landolt, Adams, Davis, et al., 2012) and fermented apple juices (Feng et al., 2018). Studies have sought to simplify the latter two lures so that they are more stable over time (Table 2).

44These lure simplifications increase the attractiveness of D. suzukii by using volatiles produced by host plants and fruits (Abraham et al., 2015; Baena et al., 2022; Bolton et al., 2019, 2022; Dewitte et al., 2021; Keesey et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018; Revadi, Vitagliano, et al., 2015; Urbaneja-Bernat et al., 2021), yeasts (Bueno et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2021; Lasa et al., 2019; Mori et al., 2017; Rehermann et al., 2022; Scheidler et al., 2015), acetic (Alawamleh et al., 2021; Ðurović et al., 2021) and lactic bacteria (Mazzetto, Gonella, et al., 2016).

Table 2. Main simplification of the attractive bait against D. suzukii and the main outcomes

|

Original attractant |

Simplication of attractant |

Outcomes |

References |

|

Wine and vinegar |

Acetic acid and ethanol |

Main constituent and responsible of the attractiveness |

(Landolt, Adams, & Rogg, 2012; Landolt, Adams, Davis, et al., 2012) |

|

Acetic acid, acetoin, ethanol, and methionol |

Attractiveness like wine and vinegar blend |

(Cha et al., 2012, 2014) |

|

|

More attractive than apple cider vinegar |

(Cha et al., 2018) |

||

|

More selective for non-target insects |

(Cha et al., 2015) |

||

|

Ethanol and acetoin |

As attractive as wine and vinegar |

(Galland et al., 2020) |

|

|

Fermented apple juice |

Acetic acid, acetoin, ethyl octanoate, ethyl acetate and phenetyl alcohol |

More attractant than apple cider vinegar |

(Larson et al., 2020) |

|

More attractive than acetic acid, acetoin, ethanol, and methionol |

(Larson et al., 2021) |

3.5.2.2. Repellent

45The main repellent odors for D. suzukii are geosmin, 1-octen-3-ol (Wallingford et al., 2016) and essential oil of peppermint (Renkema et al., 2016). Citral, known to be a repellent against many insects, is less repellent than peppermint essential oil (Galland et al., 2020). More recently, 2-penthylfuran has been shown to be more repellent than 1-octen-3-ol (Cha et al., 2021).

4. Future directions in the control of D. suzukii

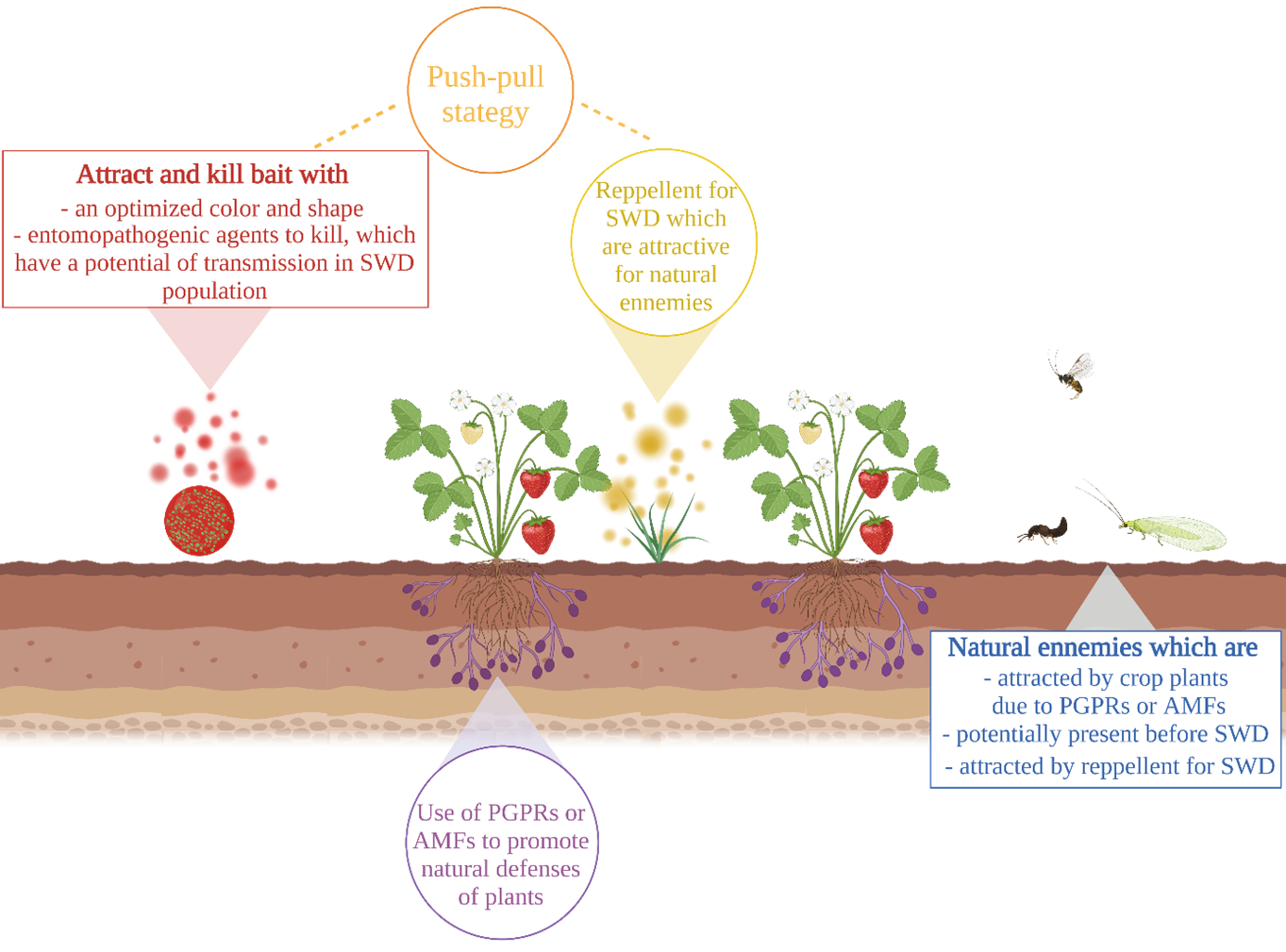

46Research on alternative methods against D. suzukii is extensive. However, very few of them combine these different methods (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Diagram of future directions in the control of Spotted Wing Drosophila (SWD). Attract and kill bait (red) associated with repellent (yellow) could induced push-pull strategy (orange). Natural defenses of plant could be increased with Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPRs) or with Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Fungi (AMFs) (purple). Attraction of natural enemies could be promoted (blue). Made with Biorender ®

4.1. Designing effective traps: associated olfactive and visual stimuli

47Visual stimuli enhance the attractiveness of SWD for semiochemicals (Basoalto et al., 2013; Iglesias et al., 2014). Blue combined with blueberry fruit odor showed synergy in one study (Keesey et al., 2019) but decreased attraction in another (Bolton et al., 2021) (Table 3).

Table 3. Main outcomes of the study by Bolton et al, 2021. For blueberry odor, the synergies are ranked in descending order

|

Odors |

Visual |

Outcomes |

|

β-cyclocitral |

Yellow |

Synergy |

|

Yeast odor (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) |

Red |

Synergy |

|

Blueberry odor |

Black |

Synergy |

|

Green |

||

|

Red |

||

|

Yellow |

||

|

Purple |

48Knowing the right associations between visual and olfactory stimuli would allow a better capture of SWD.

4.2. Push and pull: associated attractants and repellents

49Push-pull strategies combine repellents to push the pest out of the crop and outdoor attractants to attract it (Pyke et al., 1987). Repellents could also attract natural enemies of the pest to the crop, thereby increasing pest control (Fountain et al., 2021; Wallingford et al., 2018).

50Field trials of a push-pull strategy have shown low efficacy on D. suzukii (Wallingford et al., 2018). However, placing the repellents at the entrance of the crops would reduce the infestation of D. suzukii (Galland et al., 2020). In addition, the discovery of new repellents could allow a more efficient push-pull (Cha et al., 2021; Dam et al., 2019). Future research should focus on a SWD repellent that is an attractant for natural enemies.

4.3. Attract and kill: associated attractants and pathogens

51Attract and kill strategies use signals (usually semiochemicals) to attract the pest where it will encounter a toxic substance causing its death. Currently, attract and kill strategies against SWD mainly use insecticides (Babu et al., 2022; Klick et al., 2019; Rice et al., 2017). Currently, two autoinoculation devices with entomopathogenic fungi have been tested in the laboratory on SWD (Cossentine et al., 2016; Yousef et al., 2018). This research should be more important. Indeed, many pathogens, especially fungi, against SWD were discovered. Using attractants with entomopathogenic micro-organisms would reduce the use of insecticides but also be more selective than mass trapping. Indeed, generally the pathogens are specific to the pest (Cloonan et al., 2018; El-Sayed et al., 2009). Furthermore, the use of entomopathogens allows infected individuals to transmit the pathogen within the population. This would allow an even better control of the pest.

52Future research against D. suzukii should focus on the association between attractants and entomopathogens. The latter will need to be tested on beneficial insects prior to their use in the field. In addition, the transmission capacity of the pathogen within the SWD population can be evaluated.

4.4. Recruit beneficials insects: associated SWD natural enemies and natural defense of plants

53Plants naturally use Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) to defend themselves against pests. Natural enemies use these chemical signals to find their prey. In addition, these VOCs emitted by the plant give information on the identity, abundance and developmental stage of the pest (Heil & Karban, 2010; Peñaflor, 2019). Moreover, when a plant is infested, it emits specific VOCs: Herbivore Induced Plant Volatils (HIPVs). In addition to their ability to attract natural enemies, these HIPVs inform the undamaged organs of the plant, as well as other plants, of the presence of the aggressor. They also serve as a deterrent and cause behavioral changes in pests (Dicke & Baldwin, 2010; Gebreyesus Gebreziher, 2020; War et al., 2011). Recently, a study showed that the VOCs emitted by a blueberry infected with SWD were more attractive for a parasitoid than when the blueberry was not attacked (de la Vega et al., 2021).

54The study of VOCs would allow the recruitment of natural enemies (Liu et al., 2021; Rodriguez-Saona et al., 2020) potentially before the arrival of D. suzukii, thus limiting its damage. In addition, natural plant defenses (including VOC emissions) could be increased via Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPRs) and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMFs). Thus, plants could better defend themselves against SWD.

5. Conclusion

55Due to the important economic impacts and the rapid spread of D. suzukii, research concerning this pest is essential. The use of insecticides must be limited or even eliminated. Indeed, in addition to their harmful effects on the environment and human health, insecticides are less effective against SWD because this species shows resistance. Alternative methods must therefore be the priority to manage D. suzukii. Currently, cultural methods are already used. Considering the phenology of the insect, the management of wild hosts must be a priority. The application of these methods must be generalized.

56Innovative pest management biotechnologies (sterile male release, use of Wolbachia) show promising results in the control of SWD. In view of the short life cycle of the pest, these methods must prove their efficiency over several generations.

57Natural enemies (predators and parasitoids) contribute to the control of SWD. However, the lack of field trials means that their real impact on the pest population cannot be quantified. The integration of natural enemies into IPM could include the introduction of Asian larval parasitoids (classical biological control), the release of European pupal parasitoids (augmentative biological control) and the management of cultural practices to favor predators (conservation biological control). In other way, microorganisms could be associated with behavioral manipulation to increase their effectiveness.

58The next step should be the studies of the association of these methods which unfortunately is lacking for now. These must be studied to interact in synergy to have a global and effective IMP against D. suzukii.

Acknowledgments

59I warmly thank my supervisor François Verheggen for his valuable contribution. I acknowledge financial support from Région Wallone.

Further information

60ORCID identifier of author

61Chloé D Galland 0000-0003-2875-9820

62Conflicts of interest

63The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

64Abraham, J., Zhang, A., Angeli, S., Abubeker, S., Michel, C., Feng, Y. A. N., & Rodriguez-Saona, C. R. (2015). Behavioral and antennal responses of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) to volatiles from fruit extracts. Environmental Entomology, 44(2), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvv013

65Alavanja, M. C. R., Dosemeci, M., Samanic, C., Lubin, J., Lynch, C. F., Knott, C., Barker, J., Hoppin, J. A., Sandler, D. P., Coble, J., Thomas, K., & Blair, A. (2004). Pesticides and lung cancer risk in the agricultural health study cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology, 160(9), 876–885. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJE/KWH290

66Alawamleh, A., Ðurović, G., Maddalena, G., Guzzon, R., Ganassi, S., Hashmi, M. M., Wäckers, F., Anfora, G., & De Cristofaro, A. (2021). Selection of lactic acid bacteria species and strains for efficient trapping of Drosophila suzukii. Insects 2021, Vol. 12, Page 153, 12(2), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/INSECTS12020153

67Alnajjar, G., Drummond, F. A., & Groden, E. (2017). Laboratory and field susceptibility of Drosophila suzukii Matsumura (Diptera: Drosophilidae) to entomopathogenic fungal mycoses. Journal of Agricultural and Urban Entomology, 33(1), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.3954/1523-5475-33.1.111

68Altieri, M. A. (2020). How bugs showed me the way to agroecology. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 44(10), 1255–1259. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2020.1766636

69Andreazza, F., Bernardi, D., dos Santos, R. S. S., Garcia, F. R. M., Oliveira, E. E., Botton, M., & Nava, D. E. (2017). Drosophila suzukii in Southern neotropical region: current status and future perspectives. Neotropical Entomology, 46(6), 591–605. Springer New York LLC. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13744-017-0554-7

70Asplen, M. K., Anfora, G., Biondi, A., Choi, D.-S., Chu, D., Daane, K. M., Gibert, P., Gutierrez, A. P., Hoelmer, K. A., Hutchison, W. D., Isaacs, R., Jiang, Z.-L., Kárpáti, Z., Kimura, M. T., Pascual, M., Philips, C. R., Plantamp, C., Ponti, L., Vétek, G., … Desneux, N. (2015). Invasion biology of spotted wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii): a global perspective and future priorities. Journal of Pest Science, 88, 469–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-015-0681-z

71Babu, A., Rodriguez-Saona, C. R., & Sial, A. A. (2022). Comparative adult mortality and relative attractiveness of Spotted-Wing Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae) to novel Attract-and-Kill (ACTTRA SWD) formulations mixed with different insecticides. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 260. https://doi.org/10.3389/FEVO.2022.846169

72Baena, R., Araujo, E. S., Souza, J. P. A., Bischoff, A. M., Zarbin, P. H. G., Zawadneak, M. A. C., & Cuquel, F. L. (2022). Ripening stages and volatile compounds present in strawberry fruits are involved in the oviposition choice of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Crop Protection, 153, 105883. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CROPRO.2021.105883

73Ballman, E. S., Collins, J. A., & Drummond, F. A. (2017). Pupation behavior and predation on Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) pupae in Maine wild blueberry fields. Journal of Economic Entomology, 110(6), 2308–2317. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tox233

74Basoalto, E., Hilton, R., & Knight, A. (2013). Factors affecting the efficacy of a vinegar trap for Drosophila suzikii (Diptera; Drosophilidae). Journal of Applied Entomology, 137(8), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/JEN.12053

75Baulcombe, D., Crute, I., Davies, B., Dunweel, J., Gale, M., Jones, J., Pretty, J., Sutherland, W. J., & Toulmin, C. (2009). Reaping the benefits: Science and the sustainable intensification of global agriculture. https://royalsociety.org/~/media/Royal_Society_Content/policy/publications/2009/4294967719.pdf

76Bellamy, D. E., Sisterson, M. S., & Walse, S. S. (2013). Quantifying host potentials: indexing postharvest fresh fruits for spotted wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii. PloS One, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0061227

77Biganski, S., Jehle, J. A., & Kleespies, R. G. (2018). Bacillus thuringiensis serovar. israelensis has no effect on Drosophila suzukii Matsumura. Journal of Applied Entomology, 142(1–2), 33–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/JEN.12415

78Biganski, S., Wennmann, J. T., Vossbrinck, C. R., Kaur, R., Jehle, J. A., & Kleespies, R. G. (2020). Molecular and morphological characterisation of a novel microsporidian species, Tubulinosema suzukii, infecting Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 174, 107440. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JIP.2020.107440

79Bolda, M. P., Goodhue, R. E., & Zalom, F. G. (2010). Spotted Wing Drosophila: potential economic impact of a newly established pest. Agricultural and Resource Economics. Update, University of California. Giannini Foundation, 13(3), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2015.04.027

80Bolton, L. G., Piñero, J. C., & Barrett, B. A. (2021). Olfactory cues from host- and non-host plant odor influence the behavioral responses of adult Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) to visual cues. Environmental Entomology, 50(3), 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1093/EE/NVAB004

81Bolton, L. G., Piñero, J. C., & Barrett, B. A. (2022). Behavioral responses of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) to blends of synthetic fruit volatiles combined with isoamyl acetate and β-Cyclocitral. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 0, 179. https://doi.org/10.3389/FEVO.2022.825653

82Bolton, L. G., Piñero, J. C., Barrett, B. A., & Cha, D. H. (2019). Electrophysiological and behavioral responses of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) towards the leaf volatile β-cyclocitral and selected fruit-ripening volatiles. Environmental Entomology, 48(5), 1049–1055. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvz092

83Boughdad, A., Haddi, K., El Bouazzati, A., Nassiri, A., Tahiri, A., El Anbri, C., Eddaya, T., Zaid, A., & Biondi, A. (2021). First record of the invasive spotted wing Drosophila infesting berry crops in Africa. Journal of Pest Science, 94(2), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10340-020-01280-0/TABLES/2

84Briem, F., Staudacher, K., Eben, A., & Traugott, M. (2017). Habitat use and a molecular approach to analyze the diet of Drosophila suzukii. Integrated Protection of Fruit Crops IOBC-WPRS Bulletin, 123(May), 180–182.

85https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317002295

86Brilinger, D., Arioli, C. J., Werner, S. S., Rosa, J. M. Da, & Boff, M. I. C. (2021). Efficiency of attractors and traps for capture of Spotted-Wing Drosophila in vineyards. Revista Caatinga, 34(4), 830–836. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-21252021V34N410RC

87Bruck, D. J., Bolda, M., Tanigoshi, L., Klick, J., Kleiber, J., Defrancesco, J., Gerdeman, B., & Spitler, H. (2011). Laboratory and field comparisons of insecticides to reduce infestation of Drosophila suzukii in berry crops. Pest Management Science, 67(11), 1375–1385. https://doi.org/10.1002/PS.2242

88Buck, N., Fountain, M. T., Potts, S. G., Bishop, J., & Garratt, M. P. D. (2022). The effects of non-crop habitat on spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) abundance in fruit systems: A meta-analysis. Agricultural and Forest Entomology. https://doi.org/10.1111/AFE.12531

89Bueno, E., Martin, K. R., Raguso, R. A., Mcmullen Ii, J. G., Hesler, S. P., Loeb, G. M., Douglas, A. E., Mcmullen, J. G., Hesler, S. P., Loeb, G. M., & Douglas, A. E. (2019). Response of wild Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) to microbial volatiles. Journal of Chemical Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-019-01139-4

90Burrack, H. J., Asplen, M. K., Bahder, L., Collins, J. A., Drummond, F. A., Guédot, C., Isaacs, R. E., Johnson, D., Blanton, A., Lee, J. C., Loeb, G. M., Rodriguez-Saona, C. R., Timmeren, S. Van, Walsh, D. B., & McPhie, D. R. (2015). Multistate comparison of attractants for monitoring Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in blueberries and caneberries. Environmental Entomology, 44(3), 704–712. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvv022

91CABI. (2022). Drosophila suzukii (spotted wing drosophila). https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/109283 consulted 15/05/2022

92Cahenzli, F., Strack, T., & Daniel, C. (2018). Screening of 25 different natural crop protection products against Drosophila suzukii. Journal of Applied Entomology, 142(6), 563–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12510

93Calabria, G., Maca, J., Bächli, G., Serra, L., & Pascual, M. (2012). First records of the potential pest species Drosophila suzukii (Diptera : Drosophilidae ) in Europe. Journal of Applied Entomology, 136(Peng 1937), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0418.2010.01583.x

94Carrau, T., Hiebert, N., Vilcinskas, A., & Lee, K. Z. (2018). Identification and characterization of natural viruses associated with the invasive insect pest Drosophila suzukii. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 154, 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2018.04.001

95Cattel, J., Martinez, J., Jiggins, F., Mouton, L., & Gibert, P. (2016). Wolbachia-mediated protection against viruses in the invasive pest Drosophila suzukii. Insect Molecular Biology, 25(5), 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/imb.12245

96Cha, D. H., Adams, T. B., Rogg, H., & Landolt, P. J. (2012). Identification and field evaluation of fermentation volatiles from wine and vinegar that mediate attraction of Spotted Wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 38(11), 1419–1431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-012-0196-5

97Cha, D. H., Adams, T. B., Werle, C. T., Sampson, B. J., Adamczyk, J. J., Rogg, H., & Landolt, P. J. (2014). A four-component synthetic attractant for Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) isolated from fermented bait headspace. Pest Management Science, 70(2), 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/PS.3568

98Cha, D. H., Hesler, S. P., Park, S. K., Adams, T. B., Zack, R. S., Rogg, H., Loeb, G. M., & Landolt, P. J. (2015). Simpler is better: Fewer non-target insects trapped with a four-component chemical lure vs. a chemically more complex food-type bait for Drosophila suzukii. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 154(3), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/eea.12276

99Cha, D. H., Hesler, S. P., Wallingford, A. K., Zaman, F., Jentsch, P., Nyrop, J., & Loeb, G. M. (2018). Comparison of commercial lures and food baits for early detection of fruit infestation risk by Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 111(2), 645–652. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tox369

100Cha, D. H., Roh, G. H., Hesler, S. P., Wallingford, A., Stockton, D. G., Park, S. K., & Loeb, G. M. (2021). 2-Pentylfuran: a novel repellent of Drosophila suzukii. Pest Management Science, 77(4), 1757–1764. https://doi.org/10.1002/PS.6196

101Chabert, S., Allemand, R., Poyet, M., Eslin, P., & Gibert, P. (2012). Ability of European parasitoids (Hymenoptera) to control a new invasive Asiatic pest, Drosophila suzukii. Biological Control, 63(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2012.05.005

102Cini, A., Ioriatti, C., & Anfora, G. (2012). A review of the invasion of Drosophila suzukii in Europe and a draft research agenda for integrated pest management. Bulletin of Insectology, 65(1), 149–160.

103Cloonan, K. R., Abraham, J., Angeli, S., Syed, Z., & Rodriguez-Saona, C. R. (2018). Advances in the chemical Eeology of the Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) and its applications. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 44(10), 922–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-018-1000-y

104Cormier, D., Veilleux, J., & Firlej, A. (2015). Exclusion net to control spotted wing Drosophila in blueberry fields. IOBC-WPRS Bulletin, 109(2015), 181–184.

105Cossentine, J., Robertson, J. G. M., & Buitenhuis, R. (2016). Impact of acquired entomopathogenic fungi on adult Drosophila suzukii survival and fecundity. Biological Control, 103, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.09.002

106Cuthbertson, A. G. S., & Audsley, N. (2016). Further screening of entomopathogenic fungi and nematodes as control agents for Drosophila suzukii. Insects, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/insects7020024

107Cuthbertson, A. G. S., Collins, D. A., Blackburn, L. F., Audsley, N., & Bell, H. A. (2014). Preliminary screening of potential control products against Drosophila suzukii. Insects, 5(2), 488–498. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects5020488

108Daane, K. M., Vincent, C., Isaacs, R., & Ioriatti, C. (2018). Entomological opportunities and challenges for sustainable viticulture in a global market. Annual Review of Entomology, 63, 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV-ENTO-010715-023547

109Dam, D., Molitor, D., & Beyer, M. (2019). Natural compounds for controlling Drosophila suzukii. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 39(6). Springer-Verlag France. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-019-0593-z

110Dancau, T., Stemberger, T. L. M., Clarke, P., & Gillespie, D. R. (2017). Can competition be superior to parasitism for biological control? The case of spotted wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii), Drosophila melanogaster and Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 27(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2016.1241982

111de la Vega, G. J., Triñanes, F., & González, A. (2021). Effect of Drosophila suzukii on blueberry VOCs: chemical cues for a pupal parasitoid, Trichopria anastrephae. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 47(12), 1014–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10886-021-01294-7

112De Ros, G., Anfora, G., Grassi, A., & Ioriatti, C. (2013). The potential economic impact of Drosophila suzukii on small fruits production in Trentino Italy. IOBC Wprs, 10(OCTOBER)

113De Ros, G., Conci, S., Pantezzi, T., & Savini, G. (2015). The economic impact of invasive pest Drosophila suzukii on berry production in the Province of Trento, Italy. Journal of Berry Research, 5(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.3233/JBR-150092

114De Ros, G., Grassi, A., & Pantezzi, T. (2021). Recent trends in the economic impact of Drosophila suzukii. In Drosophila suzukii Management (pp. 11–27). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62692-1_2

115Dekker, T., Revadi, S., Mansourian, S., Ramasamy, S., Lebreton, S., Becher, P. G., Angeli, S., Rota-Stabelli, O., & Anfora, G. (2015). Loss of Drosophila pheromone reverses its role in sexual communication in Drosophila suzukii. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282(1804), 20143018. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.3018

116Deprá, M., Poppe, J. L., Schmitz, H. J., De Toni, D. C., & Valente, V. L. S. (2014). The first records of the invasive pest Drosophila suzukii in the South American continent. Journal of Pest Science, 87(3), 379–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-014-0591-5

117Dewitte, P., Van Kerckvoorde, V., Beliën, T., Bylemans, D., & Wenseleers, T. (2021). Identification of Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) Volatiles as Drosophila suzukii Attractants. Insects, 12(5), 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/INSECTS12050417

118Dicke, M., & Baldwin, I. T. (2010). The evolutionary context for herbivore-induced plant volatiles: beyond the “cry for help.” Trends in Plant Science, 15(3), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2009.12.002

119Diepenbrock, L. M., & Burrack, H. J. (2017). Variation of within-crop microhabitat use by Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in blackberry. Journal of Applied Entomology, 141(1–2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/JEN.12335

120DiGiacomo, G., Hadrich, J., Hutchison, W. D., Peterson, H., & Rogers, M. (2019). Economic Impact of Spotted Wing Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Yield Loss on Minnesota Raspberry Farms: A Grower Survey. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/JIPM/PMZ006

121Dos Santos, L. A., Mendes, M. F., Krüger, A. P., Blauth, M. L., Gottschalk, M. S., & Garcia, F. R. M. (2017). Global potential distribution of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera, Drosophilidae). PLoS ONE, 12(3), e0174318. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174318

122Ðurović, G., Alawamleh, A., Carlin, S., Maddalena, G., Guzzon, R., Mazzoni, V., Dalton, D. T., Walton, V. M., Suckling, D. M., Butler, R. C., Angeli, S., De Cristofaro, A., & Anfora, G. (2021). Liquid Baits with Oenococcus oeni Increase Captures of Drosophila suzukii. Insects, 12(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/INSECTS12010066

123Dyck, V. A., Hendrichs, J., & Robinson, A. S. (Eds.). (2005). Sterile insect technique (Springer).

124Ebbenga, D. N., Burkness, E. C., Hutchison, W. D., & Rodriguez-Saona, C. R. (2019). Evaluation of Exclusion Netting for Spotted-Wing Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Management in Minnesota Wine Grapes. Journal of Economic Entomology, 112(5), 2287–2294. https://doi.org/10.1093/JEE/TOZ143

125Ehler, L. E. (2006). Integrated pest management (IPM): definition, historical development and implementation, and the other IPM. Pest Management Science, 62(9), 787–789. https://doi.org/10.1002/PS.1247

126El-Sayed, A. M., Suckling, D. M., Byers, J. A., Jang, E. B., & Wearing, C. H. (2009). Potential of “lure and kill” in long-term pest management and eradication of invasive species. Journal of Economic Entomology, 102(3), 815–835. https://doi.org/10.1603/029.102.0301

127Elsensohn, J. E., & Loeb, G. M. (2018). Non-Crop Host Sampling Yields Insights into Small-Scale Population Dynamics of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura). Insects, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/INSECTS9010005

128Epstein, Y., Chapron, G., & Verheggen, F. (2021). EU Court to rule on banned pesticide use. Science, 373(6552), 290. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.ABJ9226

129Epstein, Y., Chapron, G., & Verheggen, F. (2022). What is an emergency? Neonicotinoids and emergency situations in plant protection in the EU. Ambio. 51, 1764-17771 https://doi.org/10.1007/S13280-022-01703-5

130Fanning, P. D., Grieshop, M. J., & Isaacs, R. E. (2018). Efficacy of biopesticides on spotted wing drosophila, Drosophila suzukii Matsumura in fall red raspberries. Journal of Applied Entomology, 142(1–2), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12462

131Farnsworth, D., Hamby, K. A., Bolda, M. P., Goodhue, R. E., Williams, J. C., & Zalom, F. G. (2017). Economic analysis of revenue losses and control costs associated with the spotted wing drosophila, Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura), in the California raspberry industry. Pest Management Science, 73(6), 1083–1090. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.4497

132Fauvergue, X., Rusch, A., Barret, M., Bardin, M., Jacquin-Joly, E., Malausa, T., & C. Lannou. (2020). Biocontrôle : éléments pour une protection agroécologique des cultures (Editions Quae).

133Feng, Y., Bruton, R., Park, A., & Zhang, A. (2018). Identification of attractive blend for spotted wing drosophila, Drosophila suzukii , from apple juice. Journal of Pest Science, 91(4), 1251–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-1006-9

134Follett, P. A., Swedman, A., & Price, D. K. (2014). Postharvest Irradiation Treatment for Quarantine Control of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Fresh Commodities. Journal of Economic Entomology, 107(3), 964–969. https://doi.org/10.1603/EC14006

135Foster, S. P., & Harris, M. O. (1997). Behavioral manipulation methods for insect pest-management. Annual Review of Entomology, 42, 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.ENTO.42.1.123

136Fountain, M. T., Deakin, G., Farman, D., Hall, D., Jay, C., Shaw, B., & Walker, A. (2021). An effective “push-pull” control strategy for European tarnished plant bug, Lygus rugulipennis (Heteroptera: Miridae), in strawberry using synthetic semiochemicals. Pest Management Science, 77(6), 2747–2755. https://doi.org/10.1002/PS.6303

137Foye, S., Steffan, S. A., & Bruck, D. (2020). A Rare, Recently Discovered Nematode, Oscheius onirici (Rhabditida: Rhabditidae), Kills Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Within Fruit. Journal of Economic Entomology, 113(2), 1047–1051. https://doi.org/10.1093/JEE/TOZ365

138Fraimout, A., Debat, V., Fellous, S., Hufbauer, R. A., Foucaud, J., Pudlo, P., Marin, J.-M., Price, D. K., Cattel, J., Chen, X., Deprá, M., François Duyck, P., Guedot, C., Kenis, M., Kimura, M. T., Loeb, G., Loiseau, A., Martinez-Sañudo, I., Pascual, M., … Estoup, A. (2017). Deciphering the routes of invasion of Drosophila suzukii by means of ABC random forest. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 34(4), https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx050

139Galland, C. D., Glesner, V., & Verheggen, F. (2020). Laboratory and field evaluation of a combination of attractants and repellents to control Drosophila suzukii. Entomologia Generalis, 40(3), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1127/ENTOMOLOGIA/2020/1035

140Gao, H. H., Zhai, Y.-F., Chen, H., Wang, Y. M., Liu, Q., Hu, Q. L., Ren, F. S., & Yu, Y. (2018). Ecological Niche Difference Associated with Varied Ethanol Tolerance between Drosophila suzukii and Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae). 101(3), 498–504. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.101.0308

141Gargani, E., Tarchi, F., Frosinini, R., Mazza, G., & Simoni, S. (2013). Notes on Drosophila suzukii Matsumura (Diptera Drosophilidae): Field survey in Tuscany and laboratory evaluation of organic products. Redia, 96, 85–90.

142Garriga, A., Morton, A., & Garcia del Pino, F. R. M. (2018). Is Drosophila suzukii as susceptible to entomopathogenic nematodes as Drosophila melanogaster? Journal of Pest Science, 91(2), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0920-6

143Gebreyesus Gebreziher, H. (2020). Advances in herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPV) as plant defense and application potential for crop protection. International Journal of Botany Studies, 5(2), 29–36.

144Giorgini, M., Wang, X. G., Wang, Y., Chen, F. S., Hougardy, E., Zhang, H. M., Chen, Z. Q., Chen, H. Y., Liu, C. X., Cascone, P., Formisano, G., Carvalho, G. A., Biondi, A., Buffington, M., Daane, K. M., Hoelmer, K. A., & Guerrieri, E. (2019). Exploration for native parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii in China reveals a diversity of parasitoid species and narrow host range of the dominant parasitoid. Journal of Pest Science, 92(2), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-01068-3

145Girod, P., Rossignaud, L., Haye, T., Turlings, T. C. J., & Kenis, M. (2018). Development of Asian parasitoids in larvae of Drosophila suzukii feeding on blueberry and artificial diet. Journal of Applied Entomology, 142(5), 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12496

146Goodhue, R. E., Bolda, M. P., Farnsworth, D., Williams, J. C., & Zalom, F. G. (2011). Spotted wing drosophila infestation of California strawberries and raspberries: economic analysis of potential revenue losses and control costs. Pest Management Science, 67(11), 1396–1402. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2259

147Grassi, A., Gottardello, A., Dalton, D. T., Tait, G., Rendon, D., Ioriatti, C., Gibeaut, D., Rossi-Stacconi, M. V., & Walton, V. M. (2018). Seasonal Reproductive Biology of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Temperate Climates. Environmental Entomology, 47(1), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1093/EE/NVX195

148Gress, B. E., & Zalom, F. G. (2019). Identification and risk assessment of spinosad resistance in a California population of Drosophila suzukii. Pest Management Science, 75(5), 1270–1276. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5240

149Gurr, G. M., Lu, Z., Zheng, X., Xu, H., Zhu, P., Chen, G., Yao, X., Cheng, J., Zhu, Z., Catindig, J. L., Villareal, S., Van Chien, H., Cuong, L. Q., Channoo, C., Chengwattana, N., Lan, L. P., Hai, L. H., Chaiwong, J., Nicol, H. I., … Heong, K. L. (2016). Multi-country evidence that crop diversification promotes ecological intensification of agriculture. Nature Plants, 2(3), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2016.14

150Gurr, G. M., & Wratten, S. D. (1999). FORUM ‘Integrated biological control’: A proposal for enhancing success in biological control. International Journal of Pest Management, 45(2), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/096708799227851

151Hamby, K. A., Kwok, R. S., Zalom, F. G., & Chiu, J. C. (2013). Integrating Circadian Activity and Gene Expression Profiles to Predict Chronotoxicity of Drosophila suzukii Response to Insecticides. PLoS ONE, 8(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068472

152Hamm, C. A., Begun, D. J., Vo, A., Smith, C. C. R., Saelao, P., Shaver, A. O., Jaenike, J., & Turelli, M. (2014). Wolbachia do not live by reproductive manipulation alone: Infection polymorphism in Drosophila suzukii and D. Subpulchrella. Molecular Ecology, 23(19), 4871–4885. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12901

153Hampton, E., Koski, C., Barsoian, O., Faubert, H., Cowles, R. S., & Alm, S. R. (2014). Use of early ripening cultivars to avoid infestation and mass trapping to manage Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in vaccinium corymbosum (Ericales: Ericaceae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 107(5), 1849–1857. https://doi.org/10.1603/EC14232

154Harris, P. (1991). Classical biocontrol of weeds: Its definitions, selection of effective agents, and administrative-political problems. The Canadian Entomologist, 123, 827–849.

155Hassani, I. M., Behrman, E. L., Prigent, S. R., Gidaszewski, N., Raveloson Ravaomanarivo, L. H., Suwalski, A., Debat, V., David, J. R., & Yassin, A. (2020). First occurrence of the pest Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in the Comoros Archipelago (Western Indian Ocean), 28(1), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.4001/003.028.0078

156Hauser, M. (2011). A historic account of the invasion of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in the continental United States, with remarks on their identification. Pest Management Science, 67(11), 1352–1357. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2265

157Heil, M., & Karban, R. (2010). Explaining evolution of plant communication by airborne signals. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 25(3), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.09.010

158Hogg, B. N., Lee, J. C., Rogers, M. A., Worth, L., Nieto, D. J., Stahl, J. M., & Daane, K. M. (2022). Releases of the parasitoid Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae for augmentative biological control of spotted wing drosophila, Drosophila suzukii. Biological Control, 168, 104865. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOCONTROL.2022.104865

159Homem, R. A., Mateos-Fierro, Z., Jones, R., Gilbert, D., Mckemey, A. R., Slade, G., & Fountain, M. T. (2022). Field Suppression of Spotted Wing Drosophila (SWD) (Drosophila suzukii Matsumura) Using the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT). Insects, 13(4), 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/INSECTS13040328

160Huang, J., Gut, L. J., & Grieshop, M. J. (2017). Evaluation of food-based attractants for Drosophila suzukii (diptera: Drosophilidae). Environmental Entomology, 46(4), 878–884. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvx097

161Hübner, A., Englert, C., & Herz, A. (2017). Effect of entomopathogenic nematodes on different developmental stages of Drosophila suzukii in and outside fruits. BioControl, 62(5), 669–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-017-9832-x

162Ibouh, K., Oreste, M., Bubici, G., Tarasco, E., Rossi-Stacconi, M. V., Ioriatti, C., Verrastro, V., Anfora, G., & Baser, N. (2019). Biological control of Drosophila suzukii: Efficacy of parasitoids, entomopathogenic fungi, nematodes and deterrents of oviposition in laboratory assays. Crop Protection, 125, 104897. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CROPRO.2019.104897

163Iglesias, L. E., Nyoike, T. W., & Liburd, O. E. (2014). Effect of trap design, bait type, and age on captures of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in berry crops. Journal of Economic Entomology, 107(4), 1508–1512. https://doi.org/10.1603/EC13538

164Jaffe, B. D., Avanesyan, A., Bal, H. K., Feng, Y., Grant, J., Grieshop, M. J., Lee, J. C., Liburd, O. E., Rhodes, E., Rodriguez-Saona, C. R., Sial, A. A., Zhang, A., & Guédot, C. (2018). Multistate comparison of attractants and the impact of fruit development stage on trapping Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in raspberry and blueberry. Environmental Entomology, 47(4), 935–945. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvy052

165Jarrett, B. J. M., Linder, S., Fanning, P. D., Isaacs, R., & Szűcs, M. (2022). Experimental adaptation of native parasitoids to the invasive insect pest, Drosophila suzukii. Biological Control, 167, 104843. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOCONTROL.2022.104843

166Jones, R., Fountain, M. T., Günther, C. S., Eady, P. E., & Goddard, M. R. (2021). Separate and combined Hanseniaspora uvarum and Metschnikowia pulcherrima metabolic volatiles are attractive to Drosophila suzukii in the laboratory and field. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79691-3

167Kamiyama, M. T., Schreiner, Z., & Guédot, C. (2019). Diversity and abundance of natural enemies of Drosophila suzukii in Wisconsin, USA fruit farms. BioControl, 64(6), 665–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10526-019-09966-W/TABLES/4

168Keesey, I. W., Jiang, N., Weißflog, J., Winz, R., Svatoš, A., Wang, C. Z., Hansson, B. S., & Knaden, M. (2019). Plant-based natural product chemistry for Integrated Pest Management of Drosophila suzukii. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 45(7), 626–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-019-01085-1

169Keesey, I. W., Knaden, M., & Hansson, B. S. (2015). Olfactory Specialization in Drosophila suzukii Supports an Ecological Shift in Host Preference from Rotten to Fresh Fruit. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 41(2), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-015-0544-3

170Kenis, M., Tonina, L., Eschen, R., van der Sluis, B., Sancassani, M., Mori, N., Haye, T., & Helsen, H. (2016). Non-crop plants used as hosts by Drosophila suzukii in Europe. Journal of Pest Science, 89(3), 735–748. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10340-016-0755-6/TABLES/3

171Kim, J., & Park, C. G. (2016). X-ray radiation and developmental inhibition of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae). International Journal of Radiation Biology, 92(12), 849–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/09553002.2016.1230236

172Kim, K.-H., Kabir, E., & Jahan, S. A. (2017). Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects. Science of The Total Environment, 575, 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2016.09.009

173Kirk Green, C., Moore, P. J., & Sial, A. A. (2019). Impact of heat stress on development and fertility of Drosophila suzukii Matsumura (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Journal of Insect Physiology, 114, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JINSPHYS.2019.02.008

174Kirkpatrick, D. M., McGhee, P. S., Hermann, S. L., Gut, L. J., & Miller, J. R. (2016). Alightment of Spotted Wing Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae) on Odorless Disks Varying in Color. Environmental Entomology, 45(1), 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/EE/NVV155

175Klick, J., Rodriguez-Saona, C. R., Cumplido, J. H., Holdcraft, R. J., Urrutia, W. H., da Silva, R. O., Borges, R., Mafra-Neto, A., & Seagraves, M. P. (2019). Testing a novel attract-and-kill strategy for Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) management. Journal of Insect Science (Online), 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iey132

176Klick, J., Yang, W. Q., Walton, V. M., Dalton, D. T., Hagler, J. R., Dreves, A. J., Lee, J. C., & Bruck, D. J. (2016). Distribution and activity of Drosophila suzukii in cultivated raspberry and surrounding vegetation. Journal of Applied Entomology, 140(1–2), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12234

177Knipling, E. F. (1979). The basic principles of insect population suppression and management. In Agriculture Handbook (Issue No. 512). U.S. Government Printing Office.

178Kraft, L. J., Yeh, D. A., Gómez, M. I., & Burrack, H. J. (2020). Determining the Effect of Postharvest Cold Storage Treatment on the Survival of Immature Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Small Fruits. Journal of Economic Entomology, 113(5), 2427–2435. https://doi.org/10.1093/JEE/TOAA185

179Krüger, A. P., Schlesener, D. C. H., Martins, L. N., Wollmann, J., Deprá, M., & Garcia del Pino, F. R. M. (2018). Effects of Irradiation Dose on Sterility Induction and Quality Parameters of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 111(2), 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tox349

180Labaude, S., & Griffin, C. T. (2018). Transmission Success of Entomopathogenic Nematodes Used in Pest Control. Insects, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/INSECTS9020072

181Lacey, L. A., Grzywacz, D., Shapiro-Ilan, D. I., Frutos, R., Brownbridge, M., & Goettel, M. S. (2015). Insect pathogens as biological control agents: Back to the future. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 132, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JIP.2015.07.009

182Landolt, P. J., Adams, T. B., Davis, T. S., & Rogg, H. (2012). Spotted Wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii (Diptera : Drosophilidae), trapped with combinations of wines and vinegars. Florida Entomologist, 95(2), 326–332. https://doi.org/10.2307/23268552

183Landolt, P. J., Adams, T. B., & Rogg, H. (2012). Trapping Spotted Wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae), with combinations of vinegar and wine, and acetic acid and ethanol. Journal of Applied Entomology, 136(1–2), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0418.2011.01646.x

184Lanouette, G., Brodeur, J., Fournier, F., Martel, V., Vreysen, M., Cáceres, C., & Firlej, A. (2017). The sterile insect technique for the management of the Spotted Wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii : establishing the optimum irradiation dose. PLoS ONE, 12(9), e0180821. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180821

185Larson, N. R., Strickland, J., Shields, V. D. C., & Zhang, A. (2020). Controlled-Release Dispenser and Dry Trap Developments for Drosophila suzukii Detection. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8, 45. https://doi.org/10.3389/FEVO.2020.00045/BIBTEX

186Larson, N. R., Strickland, J., Shields, V. D., Rodriguez-Saona, C. R., Cloonan, K., Short, B. D., Leskey, T. C., & Zhang, A. (2021). Field Evaluation of Different Attractants for Detecting and Monitoring Drosophila suzukii. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 175. https://doi.org/10.3389/FEVO.2021.620445/BIBTEX

187Lasa, R., Aguas-Lanzagorta, S., & Williams, T. (2020). Agricultural-Grade Apple Cider Vinegar Is Remarkably Attractive to Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophiliadae) in Mexico. Insects, 11(7), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/INSECTS11070448

188Lasa, R., Navarro-De-La-Fuente, L., Gschaedler-Mathis, A. C., Kirchmayr, M. R., & Williams, T. (2019). Yeast Species, Strains, and Growth Media Mediate Attraction of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Insects, 10(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/INSECTS10080228

189Leach, H. L., Hagler, J. R., Machtley, S. A., & Isaacs, R. (2019). Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) utilization and dispersal from the wild host Asian bush honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.). Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 21(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/AFE.12315

190Leach, H. L., Moses, J., Hanson, E., Fanning, P. D., & Isaacs, R. E. (2018). Rapid harvest schedules and fruit removal as non-chemical approaches for managing Spotted wing Drosophila. Journal of Pest Science, 91(1), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0873-9

191Leach, H. L., Van Timmeren, S., & Isaacs, R. E. (2016). Exclusion netting delays and reduces Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) infestation in raspberries. Journal of Economic Entomology, 109(5), 2151–2158. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tow157

192Lee, J. C., Bruck, D. J., Dreves, A. J., Ioriatti, C., Vogt, H., & Baufeld, P. (2011). In Focus : Spotted wing drosophila, Drosophila suzukii , across perspectives. Pest Manag Science, June, 1349–1351. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2271

193Lee, J. C., Dreves, A. J., Cave, A. M., Kawai, S., Isaacs, R., Miller, J. C., Timmeren, S. Van, & Bruck, D. J. (2015). Infestation of Wild and Ornamental Noncrop Fruits by Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 108(2), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1093/AESA/SAU014

194Lee, J. C., Wang, X. G., Daane, K. M., Hoelmer, K. A., Isaacs, R. E., Sial, A. A., & Walton, V. M. (2019). Biological control of spotted-wing drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae): current and pending tactics. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmz012

195Lee, K. Z., & Vilcinskas, A. (2017). Analysis of virus susceptibility in the invasive insect pest Drosophila suzukii. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 148(June), 138–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2017.06.010

196Lewald, K. M., Abrieux, A., Wilson, D. A., Lee, Y., Conner, W. R., Andreazza, F., Beers, E. H., Burrack, H. J., Daane, K. M., Diepenbrock, L. M., Drummond, F. A., Fanning, P. D., Gaffney, M. T., Hesler, S. P., Ioriatti, C., Isaacs, R., Little, B. A., Loeb, G. M., Miller, B., … Chiu, J. C. (2021). Population genomics of Drosophila suzukii reveal longitudinal population structure and signals of migrations in and out of the continental United States. G3 (Bethesda, Md.), 11(12). https://doi.org/10.1093/G3JOURNAL/JKAB343

197Little, C. M., Chapman, T. W., Moreau, D. L., & Hillier, N. K. (2017). Susceptibility of selected boreal fruits and berries to the invasive pest Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Pest Management Science, 73(1), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/PS.4366

198Little, C. M., Chapman, T. W., & Hillier, N. K. (2020). Plasticity Is Key to Success of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Invasion. Journal of Insect Science, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/JISESA/IEAA034

199Little, C. M., Rizzato, A. R., Charbonneau, L., Chapman, T., & Hillier, N. K. (2019). Color preference of the spotted wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52425-w

200Liu, J., Zhao, X., Zhan, Y., Wang, K., Francis, F., & Liu, Y. (2021). New slow release mixture of (E)-β-farnesene with methyl salicylate to enhance aphid biocontrol efficacy in wheat ecosystem. Pest Management Science, 77(7), 3341–3348. https://doi.org/10.1002/PS.6378